herbarium sheet

The Travelling Botanist: A Berry Good Day!

Guest blog by: Sophie Mogg

Lycium chinese, and its close relative Lycium barbarum, are both native to China although typically found to the Southern and Northern regions respectively. Part of the Solanaceae (Nightshade) family, they are also related to tomatoes, potatoes, eggplants, chili peppers, tobacco and of course belladonna. Both L. chinese and L. barbarum produces the goji berry, or among English folk commonly known as the wolfberry believed to be derived from the resemblance between Lycium and the greek “lycos” meaning wolf. Both species are decidious woody perennials that typically reach 1-3M tall however L. barbarum is taller than L. chinense. In May through to August lavendar-pink to light purple flowers are produced with the sepal eventually bursting as a result of the growing berry which matures between August and October. The berry itself is a distinctive orange-red and grape-like in shape.

In Asia, premium quality goji berries known as “red diamonds” are produced in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region of North-Central China where for over 700 years goji berries have been cultivated in the floodplains of the yellow river. This area alone accounts for over 45% of the goji berry production in China and is the only area in which practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine will source their goji berries as a result of their superior quality. The goji berry has a long history in Chinese medicine, first being mentioned in the Book of Songs, detailing poetry from the 11th to 7th century BC. Throughout different dynasties master alchemists devised treatments centering around the goji berry in order to improve eyesight, retain youthfulness and treating infertility. However it must be noted that because of the goji berry being high in antioxidants those on blood-thinning medication such as Warfarin are advised not to consume the berries.

As a result of their long standing history in Chinese medicine and their nutritional quality Goji berries have been nicknamed the “superfruit”. Many studies have linked the berries being high in antioxidants, vitamin A and complex starches to helping reduce fatigue, improve skin condition and night vision as well as age-related diseases such as Alzheimers. However, there has been little evidence to prove these claims and the evidence that is available is of poor quality.

In the 21st century the goji berry is incorporated in to many products such as breakfast biscuits, cereals, yogurt based products as well as many fruit juices. Traditionally the Chinese would consume sun-drief berries with a wide range of food such as rice congee, tonic soups, chicken and pork. Goji berries would also be boiled alongside Chrysanthemums or tea leaves from Camellia sinensis as a form of herbal tea. How would you like your berries?

I hope you have enjoyed reading about Lycium chinense and Lycium barbarum. Please complete the poll below to tell me more about what you would like to see more of.

For more information follow the links below

This entry was posted in The Travelling Botanist, Uncategorized and tagged botany, China, collections, Goji berries, Herbarium, herbarium sheet, Lycium, Manchester Museum, medicine, tea, The University of Manchester, wolfberry.

A Travelling Botanist: The Miracle Tree

Guest blog series by: Sophie Mogg

In this installment of A Travelling Botanist I will be focusing on Moringa oleifera, commonly referred to as the miracle tree.

Moringa oleifera is native to South Asia however due to the multitude of useful products it can provide its distribution has increased in more recent years and now covers the majority of Asia, Africa and Europe. M. oleifera is a hardy tree, requiring little in the way of compost or manure and being drought resistant it is well suited to the environment of developing countries. M. oleifera reaches heights of up to 3M within the first 10 months and initial harvests of leaves are able to occur between 6-8months, with subsequent yields improving as the tree reaches maturity at around 12M tall.

Many parts of the Moringa tree are utilised in South Asian cooking. The young seed pods, more often referred to as drumsticks, are used in a variety of dishes such as curries, sambars, kormas and dals. The drumsticks can also be incorporated into soups such as the Burmese Dunt-dalun chin-yei. This is true also for the fruit of the drumsticks, the white seeds can either be cooked as you would green peas or incorporated into a variety of soups. Flowers can also be used, generally being boiled or fried and incorporated into a variety of friend snacks such as pakoras and fritters or alternatively used in tea.

The leaves of the Moringa tree are considered to be very nutritional, with the suggestion that a teaspoon of leaf powder being incorporated into a meal three times a day could aid in reducing malnutrition. The leaves can be prepared in a variety of ways, from being ground into a find powder or deep-friend for use in sambals. They can also be made into a soup with the addition of rice, a popular breakfast during Ramadan. The leaves of the Moringa also contain antiseptic properties with a recent study suggesting that 4g of leaf powder can be as good as modern day non-medicated soap. This provides some means of sanitation to people who would otherwise not be able to properly clean their hands.

The seeds of a single Moringa tree can be used to provide clean water for up to 6 people for an entire year. With their outer casing removed, the seeds can be ground to form what is known as a seed cake that can be used to filter water thereby removing between 90-99% of the bacteria present. This works on the basis of attraction whereby positively charged seeds attract negatively charged bacteria and viruses causing them to coagulate and form particles known as floc. This floc then falls to the bottom of the container leaving clean water above it. It is estimated that only 1-2 seeds are required for every litre of water.

Oil is a by-product of making the seed cakes, comprising of around 40% of the seed. This oil, often known as “ben oil” by watchmakers, can serve a variety of purposes due to its properties. Due to being light, it is ideal for use in machinery and produces no smoke when lit making it ideal for oil-based lamps. The oil also contains natural skin and hair purifiers and is becoming more popular with well known cosmetic companies such as The Body Shop and LUSH thereby providing revenue to the farmers who grow the miracle tree. It also bears similarities to olive oil making it ideal for cooking and therefore another avenue for marketing this multipurpose oil.

Moringa oleifera and its close relatives are also known for their medicinal properties, containing 46 antioxidants which aid in preventing damage to cells. Due to containing benzyl isothiocyanate it has been suggested that Moringa may also contain chemo-protective properties.

I know that you may think I have completely forgotten the bark of the tree. But no, that too has its use. The tree bark is beaten into long fibres ideal for making strong rope.

I hope you have enjoyed reading about the Miracle tree as much as I have, if you wish to seek more information just follow the links below.

As always comment below with your favourite plant and if it’s in our collection and found within South Asia or Europe, I’ll be happy to feature it!

This entry was posted in Materia Medica, South Asia, The Travelling Botanist, Trees, Uncategorized and tagged botany, herbarium sheet, malnutrition, Manchester Herbarium, materia medica, medicine, miracle tree, Moringa, sanitation, sustainability, The University of Manchester, Trees.

Plant obsessions at Biddulph Grange

Last week, Daniel Atherton and Leslie Hurst from the National Trust gave us an wonderful tour of the gardens of Biddulph Grange (see Campbell’s post on the Egyptian garden here). Unfortunately, little information is available about the gardens as they were being created by the horticulturally-enthusiastic owners James and Maria Bateman (between 1840 and 1861). With the Head Gardener’s logbooks missing, the restoration of the garden has relied on other sources such as letters between Bateman, botanists and plant hunters, books logging out-going plants from specialist nurseries and descriptions from garden visitors.

The Leo Grindon Cultivated plants collection is full of specimens from notable gardens as well as a host of newspaper cuttings, magazine prints, notes and letters. With such a wealth of information, progress has been slow in documenting this collection, and so it remains an exciting treasure-trove of little-explored gems. I wondered whether there would be any references to Bateman or Biddulph Grange in the collection ….but where to start?

James Bateman is famous for his beautifully illustrated volumes on orchids, and sure enough, it wasn’t long before I uncovered some articles which Leo Grindon thought interesting enough to add into his ‘general Orchid’ selection.

This article from the Gardener’s Chronicle (Saturday, November 25th, 1871) is a biography of Bateman and his importance in the 19th century horticultural world. This quote caught my eye:

“Some of the effects, from a landscape gardener’s point of view, were strikingly beautiful, many quaint and grotesque. Had these latter been carried out by a person of less natural taste than Mr Bateman, they would have degenerated into the cockney style. In Mr Bateman’s case there was the less risk of this as, in addition to his own good taste and feeling for the appropriate, he was aided by Mr. E. W. Cooke, the eminent painter, and we may write, plant lover.”

….but I’m still not certain how complimentary this is! Another clipping touches on Bateman’s position in the debate between emerging scientific ideas and the Christian view of the creation of the earth. The geology gallery at Biddulph is a remarkable melding of Bateman’s religion with 19th century scientific discovery in stones and fossils (follow PalaeoManchester for more on this story).

Then there are a few cuttings covering James Bateman’s lectures giving summaries of the information he shared. These cuttings are typical of Leo Grindon’s collection as he rarely recorded the source of his material, or the date of publication. Presumably he was so familiar with the style of the various magazines and papers which he subscribed to that he never saw the need to write these details down.

These cuttings show that Leo Grindon was definitely following the work of James Bateman, but what of the gardens of Biddulph? For the next installment I think we shall have to move into another famous section of the garden, the Himalayan Glen, and delve into the herbarium’s Rhododendron folders to look for more clues.

To be continued……

This entry was posted in Adventures, Botanists, Collecting, Gardens, Herbarium History, Manchester Botanists, Victorian Botanists and tagged archive, Biddulph Grange, Herbarium, herbarium sheet, horticulture, James Bateman, Leo Grindon, Orchid, Orchids, Victorian botanists.

Everything in it’s place

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Of all the parts of the herbarium, our General Flowering Plants collection has had more that it’s fair share of disruption from the University’s programme of building improvements. Work began something like 7 years ago with the renovation of the tower (those crazy Victorian architects!) which meant that the three upper store rooms had to be emptied. From then until now, about half of the General Flowering Plants has been hard-stacked (box, upon box, upon box – about 800 times) and as a result, it’s been very difficult to work with.

Now that we’ve reorganised the herbarium, we finally have a shelf for every box. One of the pleasures of this is that we can now put all the herbarium sheets back in the correct place. As sheets have been returned from loans, exhibitions, events, etc. we have been accumulating ‘lay-away’ boxes with all the sheets arranged inside in taxonomic order and just waiting for the time to go back in. Thanks to our dedicated volunteers (particularly Christine) it’s all getting put safely away in the correct place.

This entry was posted in Collecting, Herbarium History, Manchester, Museums, News and tagged Box, building work, General Flowering plants, herbarium sheet, place, tower.

Powerful poppies!

by Jemma

This blog post is going to focus on a particularly interesting plant called Papaver somniferum, more commonly known as the opium poppy. Not only does this plant have a fascinating medicinal history, it also impacted heavily on us socially.

Firstly, a bit on the poppy’s medicinal use. Opium, the narcotic extracted from the plant’s seed pod, contains a number of natural painkillers and has been used in pain relief for millennia. In the 17th century, a tincture of opium combined with alcohol became readily available to the general populace under the name laudanum. Along with acting as a painkiller, laudanum was quickly employed as a cure for almost every ailment: from colds to heart problems to menstrual cramps. The drug morphine was later extracted from the opium poppy by the German pharmacist Friedrich Sertürner in the early 19th century. Morphine quickly became one of the most widely used painkillers in medicine. A further extract, called heroin, was released in 1898 by the drug company Bayer. This well known drug is now an illegal substance that is frequently abused. All of the forms of opium can be highly addictive and long term use may result in interference with the brain’s endorphin receptors. These receptors are responsible for preventing the transmission of pain signals, making withdrawal difficult.

P. somniferum use predates human recorded history and has been found in Neolithic burial sites as far back as 4,200 BC. The use of opium has been documented in numerous ancient medicinal texts including the Egyptian Ebers Papyrus from 1,500BC and those by Hippocrates in 460 BC and Dioscorides in 1st century AD.

One country that has played a big part in the history of opium is China, which was first introduced to P. somniferum between the 4th and 12th centuries via the trading route known as the Silk Road. By the 1600s, opium was smoked with tobacco and had become a popular pastime for the social elite. The recreational use of opium soon spread to the lower classes and its popularity soared. British traders from the East India Company sold large quantities of opium to smugglers to meet the growing demand for the drug. Worried by this, the Chinese Emperor began to take serious measurers to stop the illegal importation of opium, and in 1838 opium worth millions was destroyed by the Chinese Commissioner Lin Zexu.

Since opium smuggling accounted for 15-20% of income for the British Empire, they started of the First Opium War on 18th March 1839 to combat the clampdown. The British won in 1842 and implemented a series of Unequal Treaties. The first of which, the Treaty of Nanking, involved trade concessions as well as forcing the Chinese to pay a total of 21 million ounces of silver in compensation. When Britain tried to make further demands in the 1850s, the Chinese refused and the Second Opium War began. Once again, China lost and this time was forced to legalise the opium trade.

Soon opium use spread from China to the west and, as opium dens became commonplace in cities, Britain attempted to curb the use by its populace. From the 1880s onwards, they tried to reduce opium production in China by discouraging its use. However, this had the opposite effect and opium’s popularity continued to escalate. After the introduction of the more addictive heroin by Bayer, the use of opium and heroin soared even further.

In 1906, the anti-opium initiative was set up by the Chinese to attempt to eradicate the problem. The initiative tried to turn public opinion against the drug through numerous methods, such as meetings, legal action and the requiring of licence. Opium farmers had their properties destroyed, land confiscated and sometimes publically tortured in an attempt to turn the general population against using opium. Though cruel, this method was quickly deemed a success with the majority of Chinese provinces ceasing opium production. However, this success was short-lived. By 1930, China had become the primary source of opium in Eastern Asia. Today it is estimated that 27 million people[1] are addicted to opiates in one form or another and heroin continues to be a widely abused drug across the world.

Despite its chequered past and uses, the opium poppy has still contributed greatly to modern medicine and produces one of the most widely used painkillers today: morphine.

[1] According to the World Drug Report 2014 by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

This entry was posted in Materia Medica, Specimen of the Day, Students and tagged herbarium sheet, history, materia medica, medicine, morphine, museum collection, opium, pipe, poppy, war.

Siberia: At the Edge of the World Oct 2014 – Mar 2015

Tonight is the private view for our latest temporary exhibition, Siberia, after months of hard work by Dmitri Logunov and David Gelsthorpe (who have curated it) and a final few furious weeks of activity by the team who have installed it (many thanks to the collections care and access team!). There are many beautiful objects on show, but I thought I’d show a little of the preparation which went into getting one of the botanical specimens ready for display.

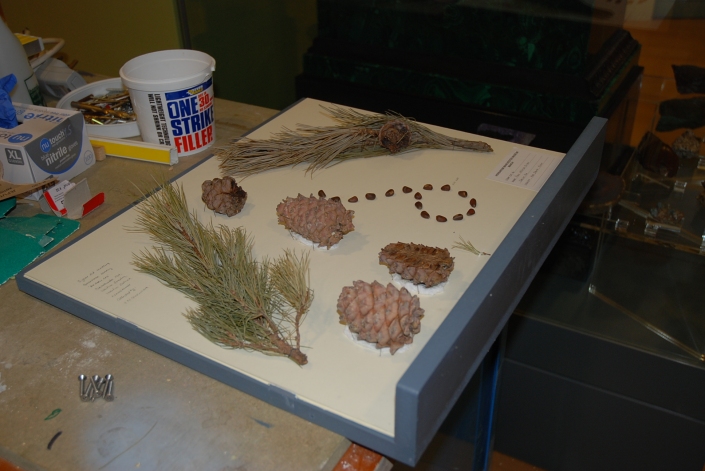

Dmitri brought some examples of Siberian pine (Pinus sibirica) to the Museum which had been collected in the Novosibirsk Region of Russia in August 2013. After a spell in the herbarium freezer to ensure that there were no insect pests, Lindsey and I put in a box for safe keeping where they waited their turn for almost a year.

A standard herbarium sheet didn’t really seem to do justice to the many pieces of tree we had acquired and as they were destined for display before incorporation into the herbarium we decided to arrange them on something bigger. We like to re-use display boxes from previous exhibitions to increase the sustainability of our displays. An acrylic box which had previously housed a stunning fan coral in the ‘Coral, something rich and strange’ seemed perfect.

With the possibilities of several branches and pine cones to choose from, mounting the specimens onto something stronger than paper also seemed like a good plan, so we asked paper conservator Dan Hogger if he could find us a suitably sized piece of cardboard. One of our regular volunteers, Christine, then tried out various bits and pieces for size to find an arrangement which looked attractive.

The task of attaching a small tree seedling, a small branch, a group of pine needles, 2 whole cones, one half eaten cone, one sectioned cone and a series of pine nuts on to the card then fell to Jemma (our placement student from Life Sciences) and myself. We decided that a combination of glue, tissue papers nests and sewing would do the job better than our standard method of gummed paper slips. We wanted to be thorough as this display is going to be attached vertically to the wall until March 2015 and I didn’t want to find myself taking it down for repairs every other week.

Then the finished piece was off to conservation to be mounted onto the backing board, and down into the exhibition space to be hung in it’s place amongst the other flora and fauna of the taiga.

This entry was posted in Exhibitions, Museums, News, Specimen of the Day, Students, Trees, University of Manchester and tagged Box, display, exhibition, glue, Herbarium, herbarium sheet, paper, pine, pine cone, Siberia, Siberian Pine, student, sustainability, world.

Beautiful Lady’s Slipper Orchids

by Rachel

The Passo Pura in the Carnic Alps was awash with summer flowers when we visited for our Field Course in Alpine Biodiversity and Forest Ecology in July. One interesting walk took us up this seasonal stream bed on the side of Monte Tinisi and rewarded us with some beautiful Lady’s Slipper Orchids (Cypripedium calceolus).

The flowers in the hot Italian sun were fading and drying up, but the plants in the shade were perfect.

I’d only ever seen this plant in cultivation before, so it was a treat to see it growing wild. In the UK it is very rare having been lost from many sites through 19th century collecting for the horticultural trade. The lady’s slipper orchid was thought extinct in the UK until a plant was found growing at one site in Yorkshire. This plant has been the focus for conservation and re-introduction programmes.

We also have pressed examples of this species in the herbarium collection and one sheet is on display in the Living Worlds gallery. This example was collected in the same area of the Carnic Alps in 1897 by James Cosmo Melville. He didn’t do a very good job of pressing the intricate 3D flowers, which is one reason why orchid flowers are often preserved in spirit collections.

This specimen collected from neighbouring Austria does a much better job of showing the structure of the flowers. However, the person who picked it also included the roots (not just examples of the leaves and flowers) which could have had consequences for the population of plants at that site. Like other orchids, germination needs the presence of a symbiotic fungus and the lady’s slipper orchid can take many years before it reaches flowering size.

This entry was posted in Adventures, Biodiversity, Botanists, Specimen of the Day, Students, University of Manchester and tagged Alpine Biodiversity, Carnic Alps, collecting, collections, conservation, Cypripedium calceolus, Field course, flower, forest ecology, Herbarium, herbarium sheet, Italy, Lady's Slipper orchid, Monte Tinisi, Orchid, Orchids, Passo Pura, pressed flower, The University of Manchester.

An introduction and how to remount specimens

Hello! My name is Jamie and I am the curatorial apprentice within the herbarium.I have been here since February and will continue to be here until the following February (2015). I have been in the herbarium for 5 months now, and we thought it was time for me to introduce myself to the blog. My first 5 months in the herbarium have involved quite a variety of different tasks. These tasks have involved relocating part of our collection to the newly installed roller racking, preparing specimens to go out for educational visits, and one of my favourites, reorganising the Materia Medica collection.

Along with the mentioned above, I have also been doing some remounting of specimens. Below you will find a selection of pictures, with a description, that shows the process of remounting a specimen. The main purpose of re-mounting specimens is for convenience in handling specimens of difficult shapes or sizes during the subsequent steps of preparation and examination. A secondary purpose is to protect and preserve the specimen as best as we possibly can.

The photo above shows the area the remounting will be taking place. Remounting is the process of replacing the cartridge paper – that the specimen is placed on – and the gummed linen tape that are no longer in a satisfactory condition.

As you can see in the first image, the specimen is placed in a flimsy folder and is not in a very good condition. In image two you can see the specimen is poorly kept, and is without any gummed tape – you can clearly see this in the image below.

As you can see in the above images this specimen clearly needs to be remounted. The first process of the remounting is to replace the sheet the specimen will be laying on, in this case from a flimsy tissue type paper, to our preferred cartridge paper. Image two shows you the new sheet for the specimen.

The above images are of the gummed tape we use – this tape is acid free and can last a very long period of time. In the second of these images you see the tape cut into thin strip, this is so we can give the specimen a snug, secure fit.

To get the gummed tape to stay secure, we have to wet both ends. But never the middle, as we don’t want to damage the specimen.

The first image above shows you how a specimen should correctly be kept. In the second image, you can see how secure the specimen looks, compared to its original sheet.

Once the specimen has a new sheet and is secure, we then have to transfer any information from its original sheet to the new one. We do this by cutting around the required information and then glue it to the new sheet, as you can see in the below image.

We then add the finishing touch, which is the Manchester Museum Herbarium stamp.

This entry was posted in News and tagged apprentice, curate, glue, Herbarium, herbarium sheet, How to, How to prepare herbarium sheets, label, paper, specimen, stamp.