Leo Grindon

Coffee or tea, madam?

It’s rather strange to think about it, but I suppose I have been living through something of a revolution in hot drinks in the UK. Traditionally, we are considered to be a nation of tea drinkers, but now on my way to work, I suspect that the majority of travel mugs clutched by my fellow commuters contain a more stimulating coffee instead. In 2008, the UK started to import more tonnes of coffee (green and roasted) than tea. Of course, you get more cups out of a kilo of tea than you do out of a kilo of coffee, but the upward trend for coffee importation continues (FAOSTAT).

It used to be that the nearest my coffee drinking came to any kind of ceremony was if I happened to be the lucky person who got to pop the seal on a new jar of instant. Now, however, even if there isn’t a gadget in the kitchen, then there’s ususally a coffee shop nearby to provide you with your morning ritual and your perfect brew. In 17th and 18th century London and Oxford, coffeehouses were also the place for men to go and read the news, make financial deals, reason about academic subjects and perhaps even discuss something a little seditious. By the end of the 18th century, these coffeehouses had all but disappeared. Many factors have been suggested for their decline, including that printed news was easier to come by, and the development of gentleman’s clubs. Tea drinking was on on the rise as it became fashionable at court, as women could participate in a way that they couldn’t in coffeehouses, and of course, through the promotional of the British East India Company’s trading interests in tea from China and particularly from India. Names such as Assam, Darjeeling, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Kangra and Niligri became familiar in the UK through the tea gardens established there by the British in the 19th century.

Easier to prepare, tea remained the hot drink of choice in the UK for about two centuries providing warmth, comfort and calories (with milk and sugar) with every cup. Many countries favour either tea or coffee at the expense of the other, and in the UK a 2012 YouGov poll still showed more people still rate a cuppa as their favourite hot drink (52% tea/ 35% coffee). The coffee shop sector is one of the strongest businesses in the UK economy, turning over £9.6 billion in 2017. So when you next get to the counter of a coffee shop, what will it be – coffee or tea?

Further reading

https://publicdomainreview.org/2013/08/07/the-lost-world-of-the-london-coffeehouse/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_coffeehouses_in_the_17th_and_18th_centuries

David Grigg (2002). The Worlds of Tea and Coffee: Patterns of consumption. GeoJournal 57; 283-294

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea_in_India

https://www.teacoffeespiceofindia.com/tea/tea-origin

Recommended by frogs and finance: Schefflera arboricola

This week I was called over to the offices of the finance team to take a look at their dwarf umbrella plant (Schefflera arboricola). It’s clearly received plenty of TLC and is thriving. However, in striving to reach the light it became too tall and very top-heavy. A bit worrying if you’re the one sitting below it! So it was time for some pruning and I’ll be taking the bits home to see if I can get some cuttings growing.

The finance team aren’t the only fans of this plant in the Manchester Museum. This beautiful little frog is a Lemur Leaf Frog; a critically endangered species which is part of the breeding programme in the newly refurbished vivarium.

The dwarf umbrella plant (S. arboricola) is a member of the Araliaceae (ivy) family and is a popular houseplant (especially in variagated forms). This specimen from our cultivated plant collection was collected in China by the plant hunter Augustine Henry (1857–1930). It is undated and was originally identified as a related plant, Heptapleurum octophyllum, but the identification has since been re-determined, as shown by the extra labels. The herbarium sheet is in our cultivated plant collection as the dwarf umbrella plant is native to Taiwan and Hainan, not the mainland Chinese province of Yunnan where this was collected.

Historic Manchester

The Manchester Histories Festival is well underway, so I think it’s time for some historically-minded posts. Leo Grindon’s Manchester Flora was published in 1859 by William White of Bloomsbury and it is ‘A descriptive list of the plants growing wild within eighteen miles of Manchester with notices of the plants commonly cultivated in gardens’. The book encourages us to ‘consider the lilies of the field’.

Along with an introduction to botany, keys to the families of plants and descriptions of species, Grindon also tells us where to go and look for these plants. So, in 1859, Ringway was the place to go and see snowdrops. I wonder if there are plenty to be found around the airport this spring?

Our copy also has an added extra tucked safely between its pages – a little bleeding heart flower (Lamprocapnos spectabilis, previously Dicentra specabilis). This plant became a popular addition to british gardens after 1846 when Robert Fortune brought it back from his travels through Japan (1812-1880). I wonder if the person who pressed it managed to identify it?

Unusual Trees to Look Out for (4)

Pterocarya fraxinifolia, Caucasian Wingnut Tree, 156/003

Meaning: winged-nut/leaves-like-an-ash-tree.

The Caucasian Wingnut tree in Beech Road Park, Chorlton, Manchester, is a particularly fine example of this specimen tree, which was sometimes planted in our Victorian and Edwardian parks. It is occasionally characteristic of the trunk of this species to divide into two main branches not far off the ground. It belongs to the walnut family (Juglandaceae) and is native to the eastern Caucasus, northern Iran and eastern Turkey. In its native habitat it can reach nearly 100 feet in height, but in northern climates it reaches about 80 feet, with a branch spread of 70 feet. Because of its nearly cubic proportions and because it is relatively fast-growing, it is prized as a shade tree. In a good year, the tree in late summer or early autumn is a delightful and strikingly decorative sight, festooned with its long, pale-green strings of seeds.

BBC Plant finder: “This superb, very large tree is rarely seen in the UK due to its enormous size: there are few gardens big enough to accommodate one. However, there are two excellent specimens in Cambridge and Sheffield Botanic Gardens that show how striking this plant can be. The tree has green leaves that can grow to over 60cm (2ft) long and that turn butter-yellow in autumn. In the summer, it produces eyecatching chains of green catkins that can grow up to 60cm (2ft) long. In its native Iran, it is often found growing by rivers, so its favoured position is in a moist, almost boggy soil where it can also get plenty of light.”

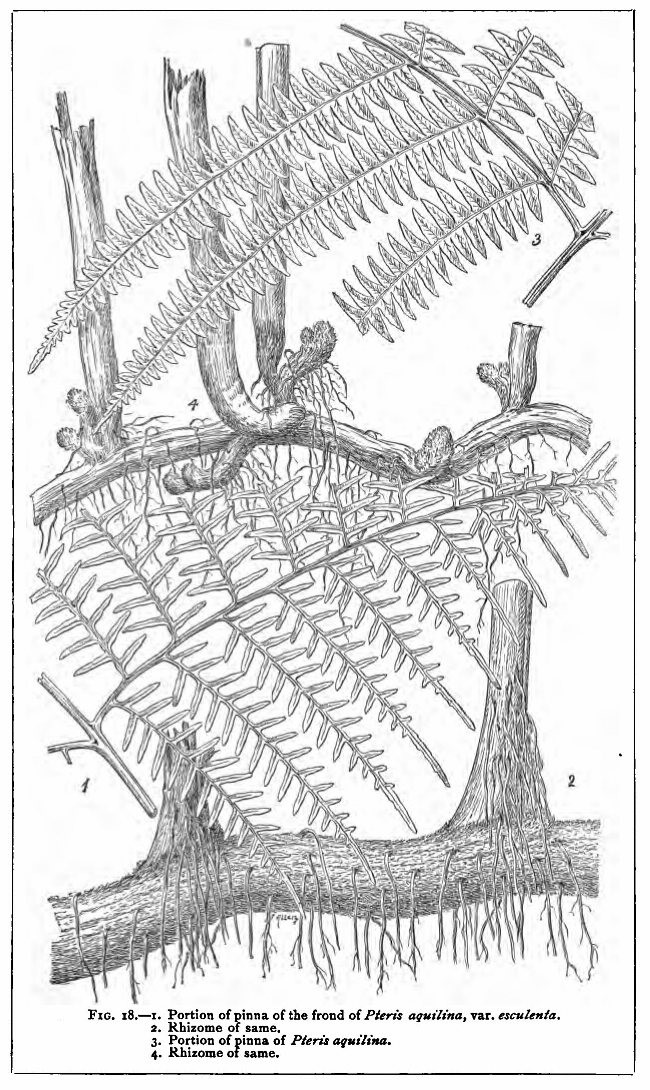

Sheets from the Grindon Herbarium

-Daniel King

Unusual Trees to Look Out for (3)

Pinus wallichiana (Pinaceae), Bhutan Pine 165/026

This one’s named after Dr. Nathaniel Wallich (1786-1854), who was born in Copenhagen but who spent much of his life exploring the botany of northern India and nearby areas. Wallich was among the most prominent botanists of his times. He introduced the seeds of this pine into England in 1827. The tree is native to the Himalaya, Karakoram and Hindu Kush mountains, from eastern Afghanistan east across northern Pakistan and India to Yunnan in southwest China. It grows in mountain valleys at altitudes of 1800-4300m (but rarely as low as 1200m), and reaches from 30-50m in height. It likes a temperate climate with dry winters and wet summers.

Our three photographs of living trees are of specimens in Sackville Gardens in the city centre and one in a churchyard in Chorlton, Manchester.

Specimen sheet from the Grindon Herbarium

-Daniel King