Manchester

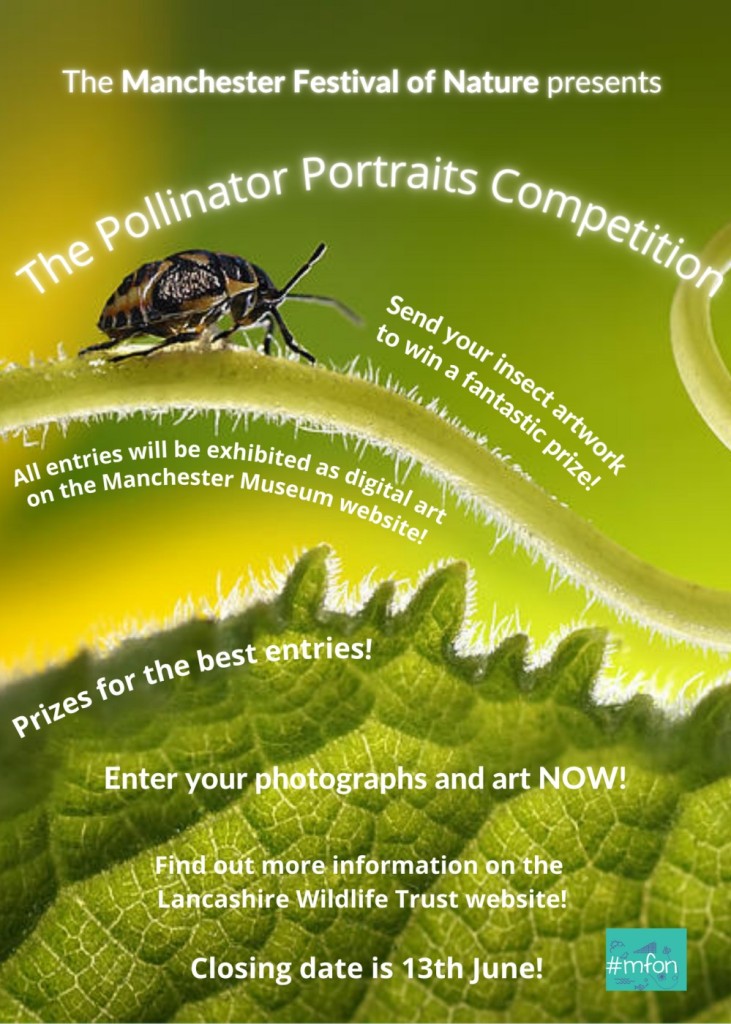

Manchester Festival of Nature 2021: Pollinator Portraits competition

Manchester Festival of Nature (MFoN), Sunday 27th June 2021

It’s been a strange time for festivals and events. Following 2019’s scorchingly hot event at Heaton Park, 2020’s Festival of Nature went entirely online with some great digital webinars and workshops, oh, and me with my first attempt at live-streaming some plant pressing. Best leave it to the professionals!

This year we again have some wonderful online content for everyone to enjoy, and we started early this year with twitter takeovers throughout the month of June.

https://twitter.com/i/events/1391444989322874883

On the day of the Festival, you can get to all the new content on our ‘main stage’ twitter account @MancNature. Also, if you are lucky enough to be taking a Sunday stroll through Heaton Park today, you might spot the Lancashire Wildlife Trust’s gazebo and chat to them about wildlife in the park.

This year, the Museum has supported the Manchester Nature Consortium Youth Panel to deliver their art competition for the Festival. Taking inspiration from the bee and insect themes of the Festival, the young people launched a Pollinator Portrait competition earlier this year. They must have faced a tough choice voting for the winners as the quality of entries was really good. The Youth Panel loved the Museum’s Beauty and the Beasts digital exhibition, so we decided to create an online exhibition to display all the works.

Head on over to our online gallery to see for yourself……..

Manchester Museum Celebrates Heritage Lottery Fund Success

Exciting changes ahead for Manchester Museum….

Manchester Museum, part of The University of Manchester, has received initial support from the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) for its Courtyard Project. The project will transform the Museum with a major two-storey extension, a new main entrance, and much-improved visitor facilities inspired by a new ethos of a ‘museum for life.’

Manchester Museum – possible perspective render

Manchester Museum – possible perspective render

Work will commence in May 2018 and the finished building will reopen in early 2020. Development funding of £406,400 has been awarded to help Manchester Museum progress its plans to apply for a full grant at a later date.

The Courtyard extension will create a major new Temporary Exhibitions Gallery, providing almost three times as much space as the Museum currently has for temporary and touring shows. The new facility will enable the Museum to become one of the North of England’s leading venues for producing and hosting international-quality exhibitions on human cultures…

View original post 284 more words

Partial solar eclipse over Manchester

The Manchester Museum came to a standstill this morning as the staff stood transfixed watching the partial solar eclipse over Manchester’s cloudy skies. Only a few hours to go until our next spectacle as the British Museum’s Moai Hava arrives from Liverpool World Museum ahead of our next temporary exhibition ‘Making Monuments on Rapa Nui‘. An exciting day for us all!