poison

The Poison Chronicles: Bryony – Deadly Margins

Guest Post by Laura Cooper

The Hours of Jeanne de Navarre is one of the most famous and beautiful illuminated manuscripts. It is a collection of prayers and psalms for each of the hours of the medieval religious day made for the personal use of the Queen of Navarre somewhere between 1328-1343. The book is lavishly and elegantly decorated with images of saints and angels framed by a naturalistic border. This curling foliage has been referred to as ivy, but was identified by Christopher de Hamel actually white bryony, Bryonia dioica.

Bryony is a notoriously poisonous plant, so the scenes the illuminator painted are far from idyllic. As de Hamel writes in his book Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts,“The world in the medieval margins is not a comfortable place, any more than the gilded life of Jeanne de Navarre was safe and secure.” Bryony is not just a decorative flourish, but a memento mori, a reminder of the danger that surrounded the medieval monarch.

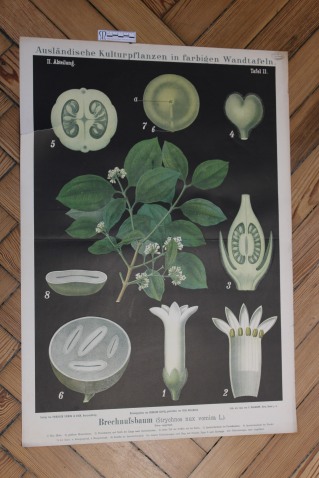

In reality, despite it’s elabourate image, bryony is an unglamourous poisoner. The plant is the only gourd (family Cucurbitaceae) native to Britain, mostly found in Central and South Eastern England. Eating the plant produces powerful laxative effect, a scatological killer not fitting the intrigue of the royal court. There doesn’t seem to be any records of human poisoning by B. dioica, but it’s occurrence in hedgerows means livestock occasionally are poisoned by the root. Historical there would have been many more cases, however. B. dioica was used as a medicine, such as for leprosy, likely as a drug of last resort for an untreatable condition.

The B.dioica plant is remarkable for its large, rapidly-growing and foul-smelling root. Roots the size of one year old child were shown to John Gerard by the surgeon of Queen Elizabeth I, William Goderous.The size and speed at which the roots can grow means that they have been used by “knaves” to counterfeit the more alleged aphrodisiac mandrake (Mandragora officinarum). In his Universal Herbal of 1832, Thomas Green describes this practice; “The method which these knaves practiced was to open the earth round a young, thriving Bryony plant […] to fix a mould, such as is used by those who make plaster figures, close to the root, and then to fill in the earth about the root, leaving it to grow to the shape of the mould.” However, the notably effects of anticholinergic toxins of mandrake, inducing hallucinations and rapid heart rate, and the laxative bryony means these frauds were unlikely to have repeat customers.

The medieval margin illustrations feature identifiable bird species, but lack botanical detail. Bryonia dioica itself is a rapid climber of hedgerows. It’s five-lobed leaves have a rough feel with curling tendrils, white flowers and red berries which produce a foetid smelling juice when squeezed. The root is usually simple like a turnip and when cut produces a white foul smelling milk from the bitter succulent flesh.

Despite its surface charms, its scent, taste and effects are the exact opposite of belladona, meaning it lacks the glamour of this more famous poisoner.

The Poison Chronicles: Hemlock

Guest Post by Laura Cooper

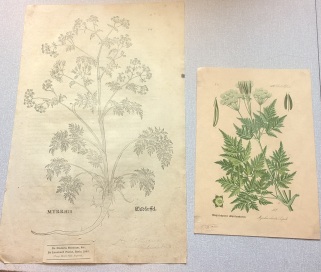

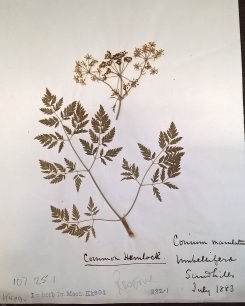

Poison hemlock (Conium maculatum) is one of the most notorious of poisonous plants. It’s best known as the poison that killed the philosopher Socrates, and may even be indirectly responsible for the deaths of quail eaters, but even this species has been used as a medicine.

Conium maculatum is in the family Apiaceae. Many species in this family resemble hemlock as they possess white flowers in umbels, branches of the stem which form a flat surface, and pinnate leaves, resemble parsely (Petroselinum crispum) and wild carrot (Daucus carota). This has lead to foragers accidentally poisoning themselves, but most are put off by the “mousy” or foetid odour and bitter taste. This and red spots that appear on the base of the plant in spring, traditionally gained when the plant grew at the base of Christ’s cross, are key identification features. It is a common “weed” globally, and was introduced as an ornamental to North America.

A vivid account of hemlock poisoning is given in Plato’s Phaedo, where his teacher Socrates is sentenced to death by consuming a “poison” known to be C. maculatum. After being given the poison, Socrates “walked about until […] his legs began to fail, and then he lay on his back […] the man who gave him the poison […] pressed his foot hard, and asked him if he could feel; and he said, No; […] and so upwards and upwards, and showed us that he was cold and stiff. And he […] said: When the poison reaches the heart, that will be the end. […] in a minute or two […] his eyes were set, and Crito closed his eyes and mouth.” The execution is an apt one for a philosopher, as he retained conscience throughout. However, the description may be idealised to preserve the dignity of Plato’s old teacher, as most hemlock poisonings involve vomiting and seizures in addition to the creeping paralysis.

Hemlock kills by a cocktail of similar chemicals, including γ-coniceine and coniine. Coniine affecting the nicotinic receptors on neurons first to stimulate the nervous system, causing seizures, vomiting and tachycardia. Later it may inhibit the central nervous system, causing brachycardia and paralysis.

One of the most sinister ways of being poisoned by a plant is the rare condition coturnism. It is caused by eating quail, Coturnix coturnix, killed in the Mediterranean whilst migrating north from Africa in the spring (but not when returning in the autumn). It is widely reported that this is due to the quail consuming the seeds of C. maculatum, but there is conflicting evidence. According to E. F. Jelliffe, hemlock drops seed in late summer and autumn, meaning quail migrating north in the spring cannot have eaten this seed. Therefore, the cause of coturnism is still a mystery.

But despite it’s notoriety, C. maculatum features in medieval household remedies. It’s powers of sedation are utilized in a recipe for an anesthetic known as dwale. The recipe involves boiling pig bile, three spoonfuls each of of hemlock juice, opium and henbane, bryony, lettuce and vinegar and adding this to half a gallon of wine. Drinking this would apparently allow a person to fall asleep and be “safely cut”, after which vinegar and salt to the face would revive them. Though the mixture seems effective at knocking a person out, it is questionable that the vinegar would be enough to revive them. However, there is no scientific evidence that “root of hemlock, digged i’ th’ dark” that the witches in Macbeth add to their potion contributed to Macbeth’s false imperviousness.

The Poison Chronicles: Aristolochia -Childbirth Aid and Carcinogen

The Aristolochia genus is particularly close to the heart of the Manchester Herbarium, its name provides us a unique Twitter nom de plume. But it is also a plant with a considerable body count. It contains a carcinogen which may be responsible for a larger number deaths than more notorious plant poisons like cyanide and ricin.

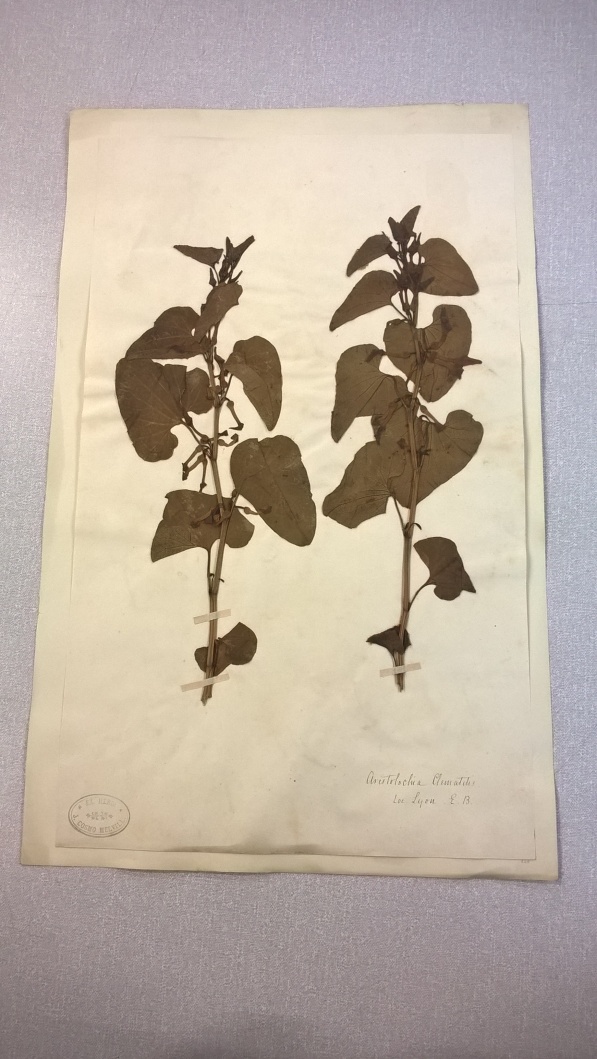

A number of species in the Aristolochia genus are known as birthwort. The genus name is derived from the Greek for “good for childbirth”, so both the common and scientific names suggests its medical use. It was noted by Roman doctors that the flowers of Aristolochia clematitis were somewhat womb-shaped. The Doctrine of Signatures, a major concept within the medicine of the time, stated that plants were designed to resemble the body part they could treat. Therefore A. clematitis roots were used for over two thousand years to trigger delayed menstruation, speed up a labour and help deliver a placenta. The plant continues to be used in Traditional Chinese Medicine and more rarely in homeopathy to treat a wide variety of diseases, despite the risks.

The roots of all Aristolochia sp. contain the carcinogen aristolochic acid, which for anyone can produce more mutations in the genome than tobacco smoke or UV light, but in the 5-10% of people who are genetically susceptible can cause kidney and urinary tract cancers. This was discovered when, in the late 1950s, localised epidemics of kidney disease and urinary tract cancer in certain rural villages in Bulgaria, Yugoslavia and Romania were noted. The condition was described as Balkan Endemic Nephropathy (BEN) but it’s cause was not found. However, in the 1990s a group of women with End Stage Renal Disease were all found to have taken the same herbal mixture for weight loss contaminated with Aristolochia fangchi, and their condition was described by researchers as Aristolochic Acid Nephropathy. When Prof Arthur Grollman from Stony Brook University learned this, he saw the similarities with BEN, and wondered if there was a similar cause. He found A. clematitis in the wheat fields of affected villages and the imprint of aristolachic acid damage in the DNA of BEN patients’ kidneys cells, showing a causal link between chronic exposure to Aristolochia and these cancers.

Aristolochia has been taken by many people as medicine or accidentally throughout history. As recently as between 1997 and 2003, an estimated 8 million people in Taiwan, were exposed to it in herbal medicine. This has lead some to suggest that it may be the most deadly plant in terms of number of fatalities rather than outright toxicity. Whether or not this claim could be quantified, it highlights that plants can be dangerous if used unwisely, so herbal medicines should not be taken blithely.

A. clematitis itself is a common weed, with creeping rhizomes and cordate (heart shaped) leaves. The distinct yellow flowers lack petals and form a tubular structure with a rounded base. Hardly notably uterine. The strange shape of the flower is due to it’s peculiar method of pollination. The hermaphroditic flowers begin first with the female stage and attract and trap flies within the flower, where they feed and spread pollen. In a few days the male stage produces the pollen that covers the trapped flies, which are released to pollinate again.

The native range is around the Mediterranean into central Europe, but was cultivated in the UK and USA. In the UK, it can be found as the survivors of the medicinal gardens of ruined nunneries and monasteries, a reminder of health care’s past and present mistakes.

For more information, see:

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/05/160503130532.htm

http://herbaria.plants.ox.ac.uk/bol/plants400/profiles/AB/Aristolochia

Sea squill, sea squill on the sea shore

by Jemma

Earlier in the month Rachel went on a trip to Mallorca, with a group of 1st year undergraduates from the University of Manchester (for more information see her blog post: https://herbologymanchester.wordpress.com/2015/04/07/surviving-salt-and-waterlogging-on-the-albuferita-mallorca/). During her time there she saw a number of sea squills (Drimia maritima) so I thought I would write a post about this interesting plant.

Drimia maritima is a poisonous plant that grows in rocky coastal habitats across southern Europe, western Asia and northern Africa. It grows from a large bulb that can be up to 20 cm wide and a kilogram in weight. In the spring, the bulb produces a rosette of dark green, leathery leaves that can reach up to a metre long. The leaves die away by autumn, when a shoot containing the flowers grows from the bulb. This flower-bearing shoot can achieve a height of up to 2 metres. Pollination of the Drimia maritima flowers occurs by both insects (specifically the western honey bee, the Oriental hornet, and the paper wasp) and wind.

Image taken from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drimia_maritima

Image taken from http://www.xericworld.com/forums/attachment.php?attachmentid=6344&stc=1&thumb=1&d=1341359115

Drimia maritima has been mentioned as far back as the 16th century BCE in the Ebers Papyrus (an ancient Egyptian medicinal text). In the 6th century BCE the Greek philosopher Pythagoras wrote about the uses of squill and, along with Dioscorides (1st century ACE and author of De Materia Medica), recommended hanging the bulb to protect against evil spirits.

One of the earliest medical applications of the sea squill came from the Greek physician Hippocrates (4th century BCE), who advocated its use to treat jaundice (yellowing of the skin), convulsions and asthma. Over the centuries, Drimia maritima was used as a common treatment for dropsy (abnormal accumulation of fluid in tissues) before the more effective foxglove (Digitalis sp.) became the standard treatment during the 18th century. The plant has also been used in folk medicine as a laxative and to clear mucus build-up.

In addition to its medicinal use, squill has been employed as a poison. All parts of the plant contain toxic chemicals. Once such compound, called Scilliroside, was shown in 1942 to be an effective rodenticide that is avoided by most other animals. In the 20th century, Drimia maritima began to be experimented on to develop highly toxic varieties for use in rat poison. Though not the most common rodenticide, interest in squill’s rat killing abilities has increased dramatically since many rats became resistant to the coumarin-based poisons previously used.

Specimen of the day – Atropa belladonna

by Jemma

Atropa belladonna, commonly called deadly nightshade, is a herbaceous perennial (which means it lives for over 2 years and its stems die down back to the soil level at the end of the growing season) in the Solanceae family. This flowering plant produces shiny black berries that are extremely toxic. There is also a second version, Atropa belladonna var. lutea, which produces pale-yellow fruit rather than the iconic black berries.

Toxicity

Atropa belladonna is well known for being one of the most toxic plants in the Eastern Hemisphere. All parts of the plant contain toxic tropane alkaloids that target the nervous system, causing increased heart rate and inhibited movement of skeletal muscle. The symptoms of belladonna poisoning are often slow to appear and include dilated pupils, sensitivity to light, tachycardia (increased heart rate), headache, hallucinations and delirium. The symptoms often last for several days, before coma and convulsions occur, followed by death. Belladonna poisoning is caused by disruptions in the regulation of involuntary activities (such as heart rate) due to the tropane alkaloids.

History of belladonna

In the middle ages, belladonna was sometimes used to make Dwale, which was an early form of herbal anaesthetic. Other ingredients in this early anaesthetic included bile, hemlock, lettuce, opium and vinegar. In addition to its use as an anaesthetic, belladonna was said to be one of the key ingredients, along with hemlock and wolfsbane, in the witches flying ointment. This magic potion supposedly allowed witches to fly on their brooms.

For centuries, small doses of belladonna have been used as a pain reliever, muscle relaxer and anti-inflammatory. Eye drops made from the plant were also used cosmetically as a method for dilating the pupils, which was considered attractive and seductive in women. To combat the toxicity of the plant, morphine from the opium poppy Papaver somniferum was used. The two plants act against each other, and were used to produce the ‘twilight sleep’. This was a dreamlike state that was utilised as a way to deaden pains and consciousness during labour. Queen Victoria famously used the ‘twilight sleep’ during childbirth. However, despite their pain relief, the drugs could affect the nervous system of the baby, resulting in a poor ability to breathe. Belladonna is still used by pharmaceutical industries today as well as in various homeopathic medicines.

Use as a poison

The most famous use for belladonna throughout history was its use as a poison. In ancient Rome, the Emperor Augustus (who defeated Mark Antony and Cleopatra) was rumoured to have been poisoned by his wife Livia in 14 AD. This resulted in her son Tiberius from a previous marriage to become the next Emperor. Another Roman Emperor supposedly murdered by belladonna was the Emperor Claudius, who was said to be killed by the poisoner Locusta on the orders of his wife Agrippina the Younger. King Macbeth of Scotland, whilst still one of the lieutenants of King Duncan I, used belladonna during a truce in order to stop the troops of the invading Harold Harefoot, who was king of England. Agatha Christie also featured belladonna in a number of her works, including The Caribbean Mystery and The Big Four.