plants

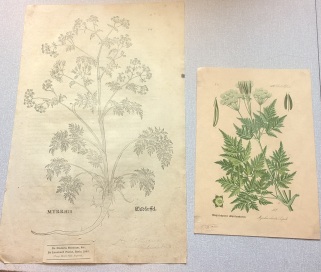

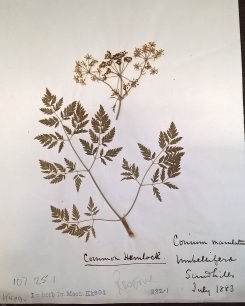

The Poison Chronicles: Hemlock

Guest Post by Laura Cooper

Poison hemlock (Conium maculatum) is one of the most notorious of poisonous plants. It’s best known as the poison that killed the philosopher Socrates, and may even be indirectly responsible for the deaths of quail eaters, but even this species has been used as a medicine.

Conium maculatum is in the family Apiaceae. Many species in this family resemble hemlock as they possess white flowers in umbels, branches of the stem which form a flat surface, and pinnate leaves, resemble parsely (Petroselinum crispum) and wild carrot (Daucus carota). This has lead to foragers accidentally poisoning themselves, but most are put off by the “mousy” or foetid odour and bitter taste. This and red spots that appear on the base of the plant in spring, traditionally gained when the plant grew at the base of Christ’s cross, are key identification features. It is a common “weed” globally, and was introduced as an ornamental to North America.

A vivid account of hemlock poisoning is given in Plato’s Phaedo, where his teacher Socrates is sentenced to death by consuming a “poison” known to be C. maculatum. After being given the poison, Socrates “walked about until […] his legs began to fail, and then he lay on his back […] the man who gave him the poison […] pressed his foot hard, and asked him if he could feel; and he said, No; […] and so upwards and upwards, and showed us that he was cold and stiff. And he […] said: When the poison reaches the heart, that will be the end. […] in a minute or two […] his eyes were set, and Crito closed his eyes and mouth.” The execution is an apt one for a philosopher, as he retained conscience throughout. However, the description may be idealised to preserve the dignity of Plato’s old teacher, as most hemlock poisonings involve vomiting and seizures in addition to the creeping paralysis.

Hemlock kills by a cocktail of similar chemicals, including γ-coniceine and coniine. Coniine affecting the nicotinic receptors on neurons first to stimulate the nervous system, causing seizures, vomiting and tachycardia. Later it may inhibit the central nervous system, causing brachycardia and paralysis.

One of the most sinister ways of being poisoned by a plant is the rare condition coturnism. It is caused by eating quail, Coturnix coturnix, killed in the Mediterranean whilst migrating north from Africa in the spring (but not when returning in the autumn). It is widely reported that this is due to the quail consuming the seeds of C. maculatum, but there is conflicting evidence. According to E. F. Jelliffe, hemlock drops seed in late summer and autumn, meaning quail migrating north in the spring cannot have eaten this seed. Therefore, the cause of coturnism is still a mystery.

But despite it’s notoriety, C. maculatum features in medieval household remedies. It’s powers of sedation are utilized in a recipe for an anesthetic known as dwale. The recipe involves boiling pig bile, three spoonfuls each of of hemlock juice, opium and henbane, bryony, lettuce and vinegar and adding this to half a gallon of wine. Drinking this would apparently allow a person to fall asleep and be “safely cut”, after which vinegar and salt to the face would revive them. Though the mixture seems effective at knocking a person out, it is questionable that the vinegar would be enough to revive them. However, there is no scientific evidence that “root of hemlock, digged i’ th’ dark” that the witches in Macbeth add to their potion contributed to Macbeth’s false imperviousness.

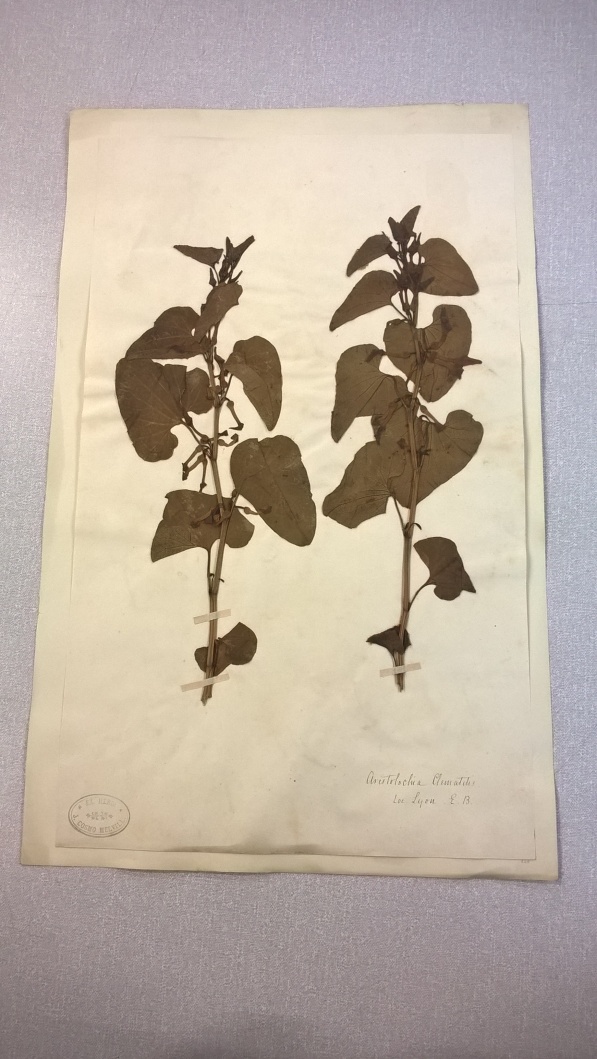

The Poison Chronicles: Aristolochia -Childbirth Aid and Carcinogen

The Aristolochia genus is particularly close to the heart of the Manchester Herbarium, its name provides us a unique Twitter nom de plume. But it is also a plant with a considerable body count. It contains a carcinogen which may be responsible for a larger number deaths than more notorious plant poisons like cyanide and ricin.

A number of species in the Aristolochia genus are known as birthwort. The genus name is derived from the Greek for “good for childbirth”, so both the common and scientific names suggests its medical use. It was noted by Roman doctors that the flowers of Aristolochia clematitis were somewhat womb-shaped. The Doctrine of Signatures, a major concept within the medicine of the time, stated that plants were designed to resemble the body part they could treat. Therefore A. clematitis roots were used for over two thousand years to trigger delayed menstruation, speed up a labour and help deliver a placenta. The plant continues to be used in Traditional Chinese Medicine and more rarely in homeopathy to treat a wide variety of diseases, despite the risks.

The roots of all Aristolochia sp. contain the carcinogen aristolochic acid, which for anyone can produce more mutations in the genome than tobacco smoke or UV light, but in the 5-10% of people who are genetically susceptible can cause kidney and urinary tract cancers. This was discovered when, in the late 1950s, localised epidemics of kidney disease and urinary tract cancer in certain rural villages in Bulgaria, Yugoslavia and Romania were noted. The condition was described as Balkan Endemic Nephropathy (BEN) but it’s cause was not found. However, in the 1990s a group of women with End Stage Renal Disease were all found to have taken the same herbal mixture for weight loss contaminated with Aristolochia fangchi, and their condition was described by researchers as Aristolochic Acid Nephropathy. When Prof Arthur Grollman from Stony Brook University learned this, he saw the similarities with BEN, and wondered if there was a similar cause. He found A. clematitis in the wheat fields of affected villages and the imprint of aristolachic acid damage in the DNA of BEN patients’ kidneys cells, showing a causal link between chronic exposure to Aristolochia and these cancers.

Aristolochia has been taken by many people as medicine or accidentally throughout history. As recently as between 1997 and 2003, an estimated 8 million people in Taiwan, were exposed to it in herbal medicine. This has lead some to suggest that it may be the most deadly plant in terms of number of fatalities rather than outright toxicity. Whether or not this claim could be quantified, it highlights that plants can be dangerous if used unwisely, so herbal medicines should not be taken blithely.

A. clematitis itself is a common weed, with creeping rhizomes and cordate (heart shaped) leaves. The distinct yellow flowers lack petals and form a tubular structure with a rounded base. Hardly notably uterine. The strange shape of the flower is due to it’s peculiar method of pollination. The hermaphroditic flowers begin first with the female stage and attract and trap flies within the flower, where they feed and spread pollen. In a few days the male stage produces the pollen that covers the trapped flies, which are released to pollinate again.

The native range is around the Mediterranean into central Europe, but was cultivated in the UK and USA. In the UK, it can be found as the survivors of the medicinal gardens of ruined nunneries and monasteries, a reminder of health care’s past and present mistakes.

For more information, see:

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/05/160503130532.htm

http://herbaria.plants.ox.ac.uk/bol/plants400/profiles/AB/Aristolochia

The Poison Chronicles: Cyanide -Cassava’s Built in Pesticide

Guest Post by Laura Cooper

I remember hearing as a small child the rumour that swallowing a single apple seed would kill you. Whilst I later learnt that this was false, it is true that the cyanide in apple seeds means that theoretically, chewing a large number could cause poisoning.

Cyanide is a simple chemical produced by many organisms, often as an unwanted by-product. But cyanide is found in relatively high levels in many plant species, including the seeds of many common food plants, such as peaches, almonds, and legumes.

The cyanogenic plant I will focus on here is cassava, Manihot esculenta, also known as yucca. It’s tubers are a major carbohydrate source throughout the tropics due to its drought tolerance and ability to thrive in poor soil. It is probably most well known in the UK in the form of tapioca pearls in puddings.

Cyanide is a general defence against herbivores, as at the right dose it can kill anything that respires. There is variation in the levels of cyanide in fresh cassava tubers, “sweet” strains have as little as 20mg/kg whilst “bitter” strains have up to 1g/kg. It has been suggested that when early farmers selected plants with the best insect resistance, they were inadvertently choosing plants containing small amounts of cyanide. This means that sometimes the decision to grow (potentially) dangerous food is not a straightforward one, and higher cyanide cassava is often preferentially planted due their greater pest resistance and drought tolerance.

One of the founding principles of toxicology is an adage derived from Paracelsus: it is the dose that makes the poison. But the case of cyanide in cassava root goes to show that it is not only the dose that matters; the ability of the host to deal with the dose can be the difference between life and death.

The lethal dose of cyanide has been reported as 1mg of cyanide ions per kg of body weight, but it is difficult to ingest this from cassava. At lower levels, chronic cyanide poisoning can have serious effects, especially in people who are already malnourished. For those with diets low in Sulphur containing amino-acids, the body cannot add the Sulphur to cyanide to make it safe. They therefore struggle to remove cyanide at amounts a healthy person could do easily, so cyanide becomes cyanate, which is associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Severe cyanide poisoning can lead to a permanent paralysis of the limbs known as Konzo, which can be fatal. Unfortunately, the hardiness of cassava means it does become relied on when other crops fail and the population is already malnourished.

However, cyanide can be removed from cassava by proper processing. Cassava stores cyanide as a chemical called linamarin, which released cyanide when hydrolysed. This occurs which can occur in the gut if ingested, or when the cassava is soaked and mashed. If done thoroughly, processed cassava is safe to eat. However, if it is done by hand, the person preparing it can inhale a considerable quantity of cyanide gas. Additionally, the water by-products of cassava processing are rich in cyanide so can be an environmental hazard.

A genetically engineered strain of cassava lacking cyanide would be a valuable crop to large agricultural companies, as it would cut down on processing time. However, for small scale farmers with poor soil, drought and no pesticides, the cyanide in cassava acts as a built in pesticide and allows cassava to thrive when little else can. This shows perfectly that poisons are not always villains, but if dealt with carefully can be a vital part of a crops’ survival tool-kit.

For more information, see this excellent article on cyanide in food plants.

The Poison Chronicles Festive edition: Poisoner and matchmaker – the joys of mistletoe

Guest blog by: Laura Cooper

Whilst many species of plants are referred to as mistletoe, the icon of Christmas is the European Mistletoe Viscum album. Mistletoe has a varied reputation; it is a symbol of Christmas and druidic ritual, a poisoner and a matchmaker.

The plant itself belongs to the Santalacea or sandalwood family. It is found throughout much of Europe, but in the UK is localized to the central south. V. album lacks its own trunk and instead grows in the crowns of host trees including apple, lime, hawthorn and poplar when its seeds are dispersed by birds smearing the sticky fruit and seed from their beaks onto the bark of the host. V. album is not a true parasite but a hemiparasite. This is because whilst the seedling sends its haustorium from the roots through the bark of the host to induce the host’s xylem vessels to supply it with water and nutrients, V. album makes its own sugars through photosynthesis. A heavy infestation of mistletoe can take over the entire crown of a tree preventing the host photosynthesising and building its own tissue which can lead to the death of the host.

V. album owes its toxicity to large amounts of the alkaloid tyramine throughout the plant, which is also present at lower levels in foods including cheese. As with most toxins, it is the dose that makes the poison, not the chemical. Whilst little research has been done on the effects of consuming V. album, it has been reported that consuming enough of the leaves or berries can result in nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea and death. However, the well-known risks of mistletoe means poisoning cases are very rare. As the Poison Garden argues, artificial mistletoe is likely more dangerous as a choking hazard to children than live mistletoe is as a poison.

Whilst mistletoe is commonly linked with druids, the only account of a druid ceremony involving mistletoe comes from Pliny the Elder. He details a banquet and ritual sacrifice where a druid would climb an oak tree, cut the mistletoe with a golden sickle and drop it into a cloak to prevent it touching the ground and losing its power. The link between druids and mistletoe was picked up in the revival of druidry in the 18th century and today druids carry out a similar ceremony, without the human sacrifice! The tradition of kissing under the mistletoe at Christmas is not a Christian tradition but also derives from the association of mistletoe with fertility in druidic mythology. Christianity has a less favorable relationship with mistletoe, as according to tradition mistletoe wood was used to makes Christ’s cross and ever since could not grow upon the earth so was condemned to parasitic life.

Mistletoe has also been used as a medicine historically, including as an epilepsy treatment. Today, injection of extracts of mistletoe has been used as an anti-cancer treatment in alternative and complementary healthcare. Whilst it has been shown to kill cancer cells, the few trials done were inconclusive or poorly done, and the NHS advises that there is currently no reliable evidence that mistletoe is effective at treating cancer.

For more mistletoe information, see:

Our green pledge at The Firs

Image Posted on Updated on

As part of our green pledge work in the museum five of us from the Collections team went to The Firs (The University of Manchester’s experimental garden).

Our job was re-potting the economic plants from a display in one of the greenhouses. Above, Henry and David mixing compost in the potting shed.

We explored the greenhouses while we were there, and came across this impressive staghorn fern (Platycerium bifurcatum). Below, carnivorous plants Venus Flytrap and a sundew, and the cactus house.

Being away from the workplace and out in the sunshine (although it was very, very cold) made it a great morning’s work. I enjoyed working with living plants, getting my hands dirty, and working with different people. The Firs is a wonderful place to visit.

Botany volunteer Barbara Porter donated her rare fern collection to the Firs when she died. It was good to see the bench dedicated to her.

Lindsey and botany intern Alyssa repotting lemongrass plants.