Manchester Botanists

Bracken

A Memoir

by Daniel Quall King

2019

This is Bracken, a Patterdale Terrier bitch,

(photographed at her hairdresser’s) who

lives with her dog, Buddy, at Abbey Farm in deepest

Norfolk. They are part of the menagerie

belonging to Richard Bales and Isabel King.

But that’s not what this is all about.

Bracken provided the word-association-football*

kickoff for this memoir, that’s all.

* A Monty Python expression

I lived in Chorlton-cum-Hardy, Manchester, from 2004 to 2010. Having been retired for some years and being fancy-free and in a place where I could pursue an old interest, geology, at university level, I proceeded to take all the geology courses then available to older folk, and even managed an OU credit.

After a couple of years of improving my knowledge of geology but having run out of adult courses, I thought I’d see if the Manchester Museum at the University of Manchester needed any volunteers in that department. They didn’t; but “Do you know anything about botany? They could do with some help.” “Well, no, but I could learn.” In this way I was set to spend some fascinating years with the people who were then the staff and volunteers in the Manchester Museum Herbarium.

I was fortunate to live on a good bus route, so once or twice a week I headed off to the university and gradually got to know my way around the herbarium.

The museum, having grown like Topsy, is a bit of a warren; the herbarium is located in the tower and attic of Manchester Museum near the entrance to the original quadrangle.

Cast of Characters (Then)

Leander Wolstenholme, Curator of Botany here giving a tour of the herbarium. A member of probably the last generation of research-centred curators, Leander was one of those people with an extraordinary memory for all things botanical. For some years he was an editor of the Journal of the Botanical Society of the British Isles. A person of great kindness and humour.

Lindsey Loughtman, the ever-helpful Curatorial Assistant (part-time).

Suzanne Grieve, Curatorial Assistant (part-time).

Matt Lowe, Curatorial Assistant (later at the Zoological Museum, University of Cambridge).

Priscilla Tolfree, retired university librarian and lifelong plant enthusiast.

Audrey Locksley, Patricia’s botany pal and another very knowledgeable amateur.

Barbara Porter, who collected rare ferns and had a garden full of them which she bequeathed to the University. We transplanted them to the university’s Botanical Experimental Ground in Fallowfield.

Dave Bishop (Retired industrial chemist, Mersey Valley botany expert).

David Earl, County Recorder for both the Lancashire vice counties (S, 59 & W, 60); another botanist with a remarkable memory. Fondly referred to by Patricia as ‘the fount of all knowledge’.

Daniel King, rank amateur, but very curious.

The story of the founding of the MMHerb is interesting enough, and a potted version of it is included at the end of this memoir. Once Matt Lowe trained me up to take photos and put them online at http://harbour.man.ac.uk/mmcustom/BotQuery.php , most of the material I was put to work on was in the Grindon Herbarium, a unique collection of specimens, illustrations and printed material.

However, that’s just to get the ball rolling. Or the seed germinating (sorry).

One morning I de-bussed as usual at Oxford Road and made my way to the quad and up to the herbarium for a morning of photography and putting-on-line. But when it came time for cuppas, up on the raised bit of platform that accommodated a couple of office desks and enough seats for a tea-break, sitting in a group approximating the demeanour of a court martial were Suzanne, Leander and Lindsey. I negotiated the steps and made for the kettle, but before I could do anything with it, an ominous “Dannn … ” with interesting inflections emerged from Lindsey. No-one cracked a smile. So I smiled and said “Hi!”, thinking, ‘This is serious’. And I hadn’t even dropped the camera. “We’ve got a proposal for you. You know the illustrations in the Grindon Herbarium? We thought you might be interested in identifying the publications they were taken from.” Nonplussed, I was, thinking the trio had misidentified me as the Yoda of the graphic world. The Grindon Herbarium isn’t small, and over the many years Leopold Hartley Grindon had assembled the material, there must have accumulated many hundreds, perhaps thousands, of loose illustrations and articles taken from damaged or incomplete botanical books. What a job that’d be! All I could do was look at Leander and ask, “How long do you think it would take?” He looked away thoughtfully for a few seconds, and then, back in eye contact, he said “Maybe three or four years”.

To make a long story somewhat shorter, the main result of a couple of years of research was two articles, with checklists, about the Grindon Herbarium and the sources of the illustrative and other material it contains. There are materials from 24 of the popular botanical periodicals of the day; and from books and serial publications, 78 (published 2007) in Archives of Natural History and another 17 (2009) for a total of 95. Of course, never having submitted an article for publication in a scholarly periodical, I relied a great deal on advice from Leander about the commentary in the articles.

We were all very pleased when the articles were accepted. They are in ANH Vol. 34 (1): 129-139, April 2007, and Vol. 36 (2): October 2009. The latter is in the Short Notes section, p.354 ff. Archives of Natural History is published by The Society for the History of Natural History (yes, really), which has offices in the Natural History Museum in London. This may be one of the least-known scholarly publications in the world, but has fascinating articles about such things as the great voyages of discovery and so forth. For the enthusiast, the Manchester Museum Collections Database contains within a larger number, the original 700 or so images from the Grindon. If you type botanical prints and drawings into the Botany search window, it brings up most of them.

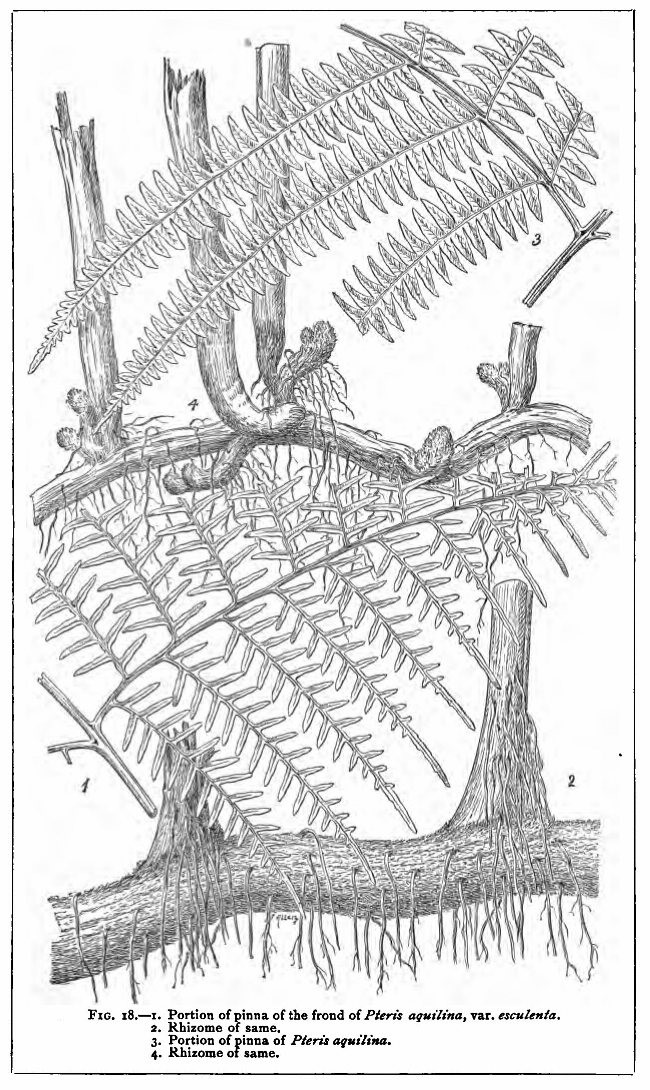

So what happened to the bracken? When Bracken the pup got her name, it eventually reminded me of an item in Grindon – a pair of exquisite pen-and-ink drawings on tracing paper, as well as a set of printer’s proofs, of Pteridium aquilinum, or bracken to you and me. According to my information, the spores of ordinary bracken are so light that they’ve spread to all corners of the botanical globe, including the often very isolated islands of the South Atlantic. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pteridium_aquilinum .

Although the original photo files of the illustrations are large and adequate to do justice to the extremely fine work in them, the software that uploads them into the KE Emu database condenses the information to such an extent that the delicacy and detail in the original are lost.

Here’s what the online photo of the original looks like:

But what a good excuse to visit the herbarium and see the originals! The illustrations were made for the translation of Julien Marie Crozet’s 1771-1772 account of his voyage of discovery to the South Atlantic, published in 1891. Here’s the relevant section:

http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks13/1306431h.html yields: H. Ling Roth, transl., Crozet’s Voyage to Tasmania, New Zealand the Ladrone Islands, and the Philippines in the Years 1771-1772. London: Truslove & Shirley, 143, Oxford Street, W.; 1891. p35ff:

The Food of the Inhabitants of the North of New Zealand.

We were extremely well received by the savages. They came in mobs on to the vessels and appeared there every day, and we went similarly to their villages and into their houses with the greatest security. This naturally gave us every facility for seeing how these people fed themselves, what were their occupations, their works, their industry, and even their amusements.

We have already noticed that the basis of the food of these people is the root of a fern absolutely similar to ours, with the sole difference that in some places the New Zealand fern has a much bigger and longer root and its fronds grow to greater length.[1]

[1 The New Zealand fern is Pteris aquiline, var. esculenta, and the European species is Pteris aquiline. The difference is thus very slight. See Figs. 17 and 18.]

Having pulled up the root they dry it for several days in the air and sun. When they wish to eat it they hold it before the fire, roast it lightly, pound it between two stones, and when in this state they chew it in order to obtain the juices, which to me appeared farinaceous; when they have nothing else to eat, they eat even the woody fibre; but when they have fish or shellfish or some other dish, they only chew the root and reject the fibre.

These people live also principally on fish and on shellfish; they eat quail, ducks and other aquatic birds which abound in their country, also various species of birds, dogs, rats, and finally they eat their enemies.

The New Zealanders have no vessel in which to cook their meat; the general custom in all the villages we visited was to cook the meat and fish in a sort of subterranean oven. In every kitchen there is a hole one and a half feet deep and two feet in diameter; on the bottom of the hole they place stones, on the stones they place wood which they light, on this wood they place a layer of flat stones which they make red hot, and on these latter stones they place the meat or fish which they desire to cook.

They also live on potatoes and gourds, which they cook in the same way as their meat. Their habits in eating are dirty.

I have also seen them eat a sort of green gum which they like immensely, but I was not able to find out the tree from which they obtained it. Some of us ate of this by letting it drop in our mouths. We all found it very heating.

We also remarked that the savages eat regularly twice a day, once in the morning, the other time at sunset. As they are all strong, hardy, big, well-formed, and with good constitution, one concludes that their food is very healthy, and I think it well to repeat here that fern root forms the basis of their food.

Generally speaking they appeared to me to be great eaters; when they came on board our vessel, we could not satisfy them sufficiently with the biscuit which they liked immensely. When the sailors were eating they would approach them in order to get a portion of their soup and of their salt meat. The sailors used to give them the remains on their platters, which the savages took care to clean out thoroughly; they were very fond of fat and even of tallow. I have even seen them take the tallow from the sounding lead or tallow otherwise used in the ship and eat it as a tasty morsel. They were very partial to sugar; they drank tea and coffee with us, and liked our drinks according as they were more or less sweetened. They showed great repugnance for wine, and especially for strong liquors; they do not like salt and do not eat it. They drink a great deal of water, and when I saw them very thirsty, I used to think that this desire to be continually drinking was caused by their dry food, the fern root.

The Manchester Museum Herbarium

The MANCH [coded for reference] herbarium is held within The Manchester Museum, part of The University of Manchester. It contains approximately 1 million specimens covering a world-wide distribution. It was founded in 1860 by the coalition of several major individual or corporate collections. In particular, the two nineteenth-century Manchester businessmen and amateur naturalists, Charles Bailey and Cosmo Melvill, inspired by the original and substantial collections of the Manchester Natural History Society, collaborated to collect and buy plant material from around the world, and arranged for their final deposition at the Museum. Bailey and Melvill alone provided a wide range of plant collections unequalled by any but a few major national museums. Also, at that time the museum acquired the very special collection of plants, many cultivated, together with illustrations and text, that were assembled by Leo Grindon in connection with his pioneering work in Adult Education.

In addition to this foundation material, the Museum’s Herbarium incorporates collections from thousands of other people, ranging from small personal herbariums donated or bequeathed, to material collected today by expeditions to tropical rain forests and other endangered habitats. There are also many items of historical importance and interest, such as specimens collected by Charles Darwin during the voyage of the Beagle, specimens collected by Admiral Franklin’s expeditions in search of the N.W. Passage, and collections of the great Swedish naturalist Linnaeus. In particular, the 16,500 Richard Spruce items (mostly Amazon and Andes hepatics) have a value far in excess of their number.

DQK Note: At the time when I worked there, the herbarium collection was reckoned to be the fourth largest in the British Isles. Some of the others are at London (Kew and the Natural History Museum), Glasnevin, Edinburgh and Cambridge. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_herbaria_in_Europe#British_Isles .

This entry was posted in Herbarium Films, Herbarium History, Manchester, Manchester Botanists, Manchester Museum, Victorian Botanists and tagged Database, dog, Leo Grindon, photography.

Plant obsessions at Biddulph Grange

Last week, Daniel Atherton and Leslie Hurst from the National Trust gave us an wonderful tour of the gardens of Biddulph Grange (see Campbell’s post on the Egyptian garden here). Unfortunately, little information is available about the gardens as they were being created by the horticulturally-enthusiastic owners James and Maria Bateman (between 1840 and 1861). With the Head Gardener’s logbooks missing, the restoration of the garden has relied on other sources such as letters between Bateman, botanists and plant hunters, books logging out-going plants from specialist nurseries and descriptions from garden visitors.

The Leo Grindon Cultivated plants collection is full of specimens from notable gardens as well as a host of newspaper cuttings, magazine prints, notes and letters. With such a wealth of information, progress has been slow in documenting this collection, and so it remains an exciting treasure-trove of little-explored gems. I wondered whether there would be any references to Bateman or Biddulph Grange in the collection ….but where to start?

James Bateman is famous for his beautifully illustrated volumes on orchids, and sure enough, it wasn’t long before I uncovered some articles which Leo Grindon thought interesting enough to add into his ‘general Orchid’ selection.

This article from the Gardener’s Chronicle (Saturday, November 25th, 1871) is a biography of Bateman and his importance in the 19th century horticultural world. This quote caught my eye:

“Some of the effects, from a landscape gardener’s point of view, were strikingly beautiful, many quaint and grotesque. Had these latter been carried out by a person of less natural taste than Mr Bateman, they would have degenerated into the cockney style. In Mr Bateman’s case there was the less risk of this as, in addition to his own good taste and feeling for the appropriate, he was aided by Mr. E. W. Cooke, the eminent painter, and we may write, plant lover.”

….but I’m still not certain how complimentary this is! Another clipping touches on Bateman’s position in the debate between emerging scientific ideas and the Christian view of the creation of the earth. The geology gallery at Biddulph is a remarkable melding of Bateman’s religion with 19th century scientific discovery in stones and fossils (follow PalaeoManchester for more on this story).

Then there are a few cuttings covering James Bateman’s lectures giving summaries of the information he shared. These cuttings are typical of Leo Grindon’s collection as he rarely recorded the source of his material, or the date of publication. Presumably he was so familiar with the style of the various magazines and papers which he subscribed to that he never saw the need to write these details down.

These cuttings show that Leo Grindon was definitely following the work of James Bateman, but what of the gardens of Biddulph? For the next installment I think we shall have to move into another famous section of the garden, the Himalayan Glen, and delve into the herbarium’s Rhododendron folders to look for more clues.

To be continued……

This entry was posted in Adventures, Botanists, Collecting, Gardens, Herbarium History, Manchester Botanists, Victorian Botanists and tagged archive, Biddulph Grange, Herbarium, herbarium sheet, horticulture, James Bateman, Leo Grindon, Orchid, Orchids, Victorian botanists.

Baking botanists in the Cala de Bocquer

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Yesterday saw a group of first-year undergraduates braving the baking Mediterranean sun for the first day trip of the Comparative and Adaptive Biology field course. The Bocquer Valley near the town of Pollenca is a great place to look for Mallorcan endemic ‘hedgehog’ plants Teucrium subspinosum and Astragalus balearicus. While the students investigated the distribution of these small spiny shrubs, the staff took the opportunity to do a little more plant hunting.

One beautiful plant we regularly see in flower is the Balearic cyclamen (Cyclamen balearicum). It has very marbled leaves and delicate white flowers and hides in the shade of the larger shrubs. We also find the leaves of the Mallorcan peony (Paeonia cambessedessii). We visit far too late to see it in flower, but we’ve never found fruit either, suggesting that these plants didn’t flower in February or March. Perhaps these are young plants, or perhaps this is an indication of the difficult environment in the valley. This peony is named for the French botanist Jacques Cambessedes (1799-1863) who studied the plants of the Balearic Islands in 1825 and published the account of his travels and his work on the flora in 1826 and 1827.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

One plant we’ve not spotted on our previous visits is the Dead-horse arum (Helicodiceros muscivorus). Given that it was behind a tree, under a shrub and in the bottom of a drainage channel, it’s not too surprising that we’ve not found it before. This plant has striking arrow-shaped leaves (sagittate leaves) and a flower spike (spadix) enclosed in a sheath known as a spathe. This specimen had not yet opened, and the geometrically patterned spathe was still closed shut. I’m not sure that I was too disappointed as the plant attracts pollinating flies with heat and rotting carcass smells.

This entry was posted in Adventures, Biodiversity, Botanists, Manchester Botanists, Students, University of Manchester and tagged cyclamen, dead-horse arum, distribution, Mallorca, Mediterranean, peony, plant, student, sun.

The mysterious Miss Wigglesworth

by Jemma

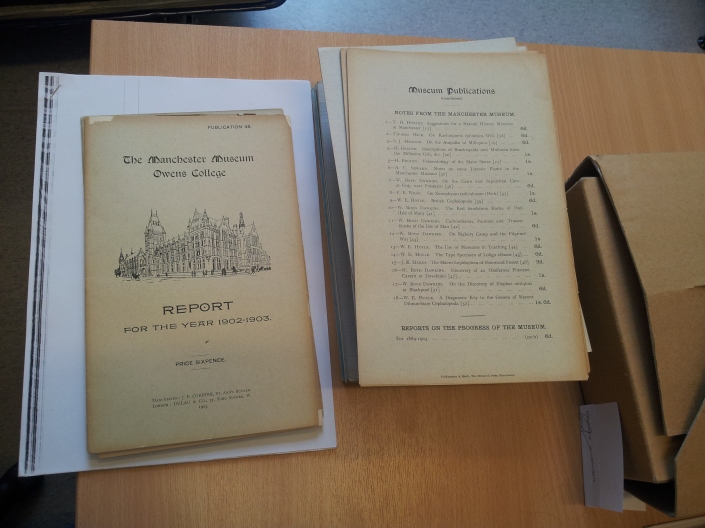

For the past few days I have been digging through the Museum’s annual reports from the 19th-20th century. During my search one name kept cropping up: Miss Wigglesworth. She was in every report for a long period of time so I decided to look into her.

Grace Wigglesworth was a student at Owens College from 1900 (which became The Victoria University of Manchester in 1904 and would later become the University of Manchester). She graduated with a B.Sc (Hons) in Botany in 1903 and later gained a Master’s degree in palaeobotany.

In 1908 she was admitted as a fellow in the Linnean Society of London, which housed (and still does) the collection and personal library of the father of modern taxonomy Carl Linnaeus. In January 1911, Wigglesworth was appointed Assistant Keeper of botany at the Manchester Museum. Assistant Keepers were in charge of curating the collections. During her time as Keeper, Wigglesworth cared and organised the museum’s collections, worked on gallery displays and lectured at the University.

Wigglesworth was the second female within the Herbarium staff and held the post for 33 years. Even after she retired in 1944, Wigglesworth continued to help around the Herbarium until the 1950’s.

This entry was posted in Botanists, Female Botanists, Herbarium History, Manchester, Manchester Botanists, Museums, Students, University of Manchester and tagged 20th century, botany, curator, Keeper, Linnean Society, Manchester Museum, museum collection, University of Manchester.

Transferring from Newspaper – by Jamie Matley

We come across plenty of specimens placed in newspapers – this one is from 1912! – Not all of them, like this one, are secured with tape. But, when they do have tape, we have to cut through the tape with either a knife (pictured) or a scalpel.

Once the specimen has been cut free; we then transfer the specimen to a new sheet.

Along with the specimen, we transfer all identifiable information to the new sheet.

The finished product, the specimen on its new sheet, secured with tape, and with the same information from its previous (newspaper) sheet.

This entry was posted in Herbarium History, Manchester Botanists, University of Manchester, Victorian Botanists and tagged apprentice, Herbarium, label, Manchester, newspaper, plant, scissors, specimen.

The Roller Racking’s Arrived!

Aside Posted on Updated on

It’s been a hectic start to 2014 at the herbarium! Following the break for Christmas and New Year we had some fantastic roller racking installed. The racking was salvaged from the Whitworth art gallery following their redevelopment. The room overlooking the Old Quad was cluttered with all sorts of specimens. It was previously home to Algae amongst others in grand old cupboards. It took a while, and a huge moving effort from the team, but after a couple of days we had managed to: temporarily re-house our solander boxes in a temporary makeshift home, clear out the vast runs of journals and books hidden behind shelves and finally we had fully cleared the room ready for the installation team.

Now that the roller racking is installed it allows us to make much more efficient use of the space we have. Our solander box collections can now be stored in a greatly compact way, whilst still allowing access when necessary. There are 8 new shelving units in the roller racking, each with the capacity to store 97 solander boxes. Whilst the permanent occupants of the racking have not yet been decided, the increased storage capacity has allowed us to begin the plans to re-organise the entire collections into a more logical and flowing way

The job of re-arranging our collections has not been an easy one. Lots of number crunching has taken place. The aim is to get all the collections more efficiently organised and to work the boxes that currently take up our work bench space into the collections on the racking. The project will involve each box in the entire collection moving to a new place. So there is going to be a lot of hard work, moving around and re-jigging in the coming months, but it will worth it in the end.

This entry was posted in Herbarium History, Manchester, Manchester Botanists, Roller Racking, Uncategorized, University of Manchester and tagged botany, Herbarium, Manchester, museum, racking, roller, shelving, Whitworth Art Gallery.

Manchester Herbarium

A lovely review of a visit to our herbarium from the blog of Tim Body: Manchester Herbarium. Tim is an MMU ecology student and his blog From here to ecology is well worth a read.

This entry was posted in Identification, Manchester Botanists, Students.

Breaking News on our Mystery Botanist

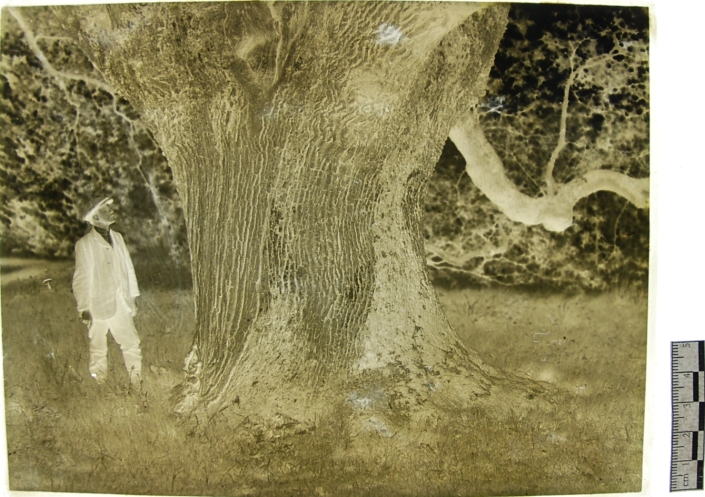

Earlier this year we posted a photograph of a portrait we found in a box of paperwork at the back of the herbarium. It clearly shows a Victorian botanist – but which one? We speculated that it might look like Richard Buxton, who was a very interesting and impressive self-taught naturalist, but we now have another contender.

Christine Walsh (one of our dedicated team of herbarium volunteers) came across a picture of Joseph Evans (1803 – 1874), botanist and herbal doctor from Boothstown. There’s a biography of him on this site, and I have to say, he looks very like our mystery man. What do you think?

This entry was posted in Manchester, Manchester Botanists, News, Victorian Botanists and tagged Artisan botanist, botanical societies, Manchester, working class botanists.

Is that Richard Buxton’s nose?

Rummaging through a box at the back of the herbarium earlier today we came across this lovely painting of a botanist (nothing like having a fern in the lapel to demonstrate your occupation!).

Looking at a display panel in the herbarium, we thought the man in the portrait looks rather similar to the daguerreotype of Richard Buxton aged 65 (on the right). What do you think?

Richard Buxton (1786 – 1865) was a very interesting man, born in Prestwich and apprenticed to be a children’s shoemaker, he decided to teach himself to read. From there, he moved on to educating himself about the plants he found growing around him, firstly by reading Culpeper’s Herbal, before reading more scientific texts which explained the Linnaean system for classifying plants. He became a renowned local botanist and wrote floras of the plants found around Manchester. We are proud to have plant material collected by such a remarkable man in our herbarium collections, and so we have some out on display in our Manchester Gallery.

This entry was posted in Herbarium History, Manchester, Manchester Botanists, News and tagged painting, Prestwich, Richard Buxton, Victorian botanists, working class botanists.

Internship at the Herbarium.

Hello, my name is Nicole and over the past couple of months I’ve been an intern at the Manchester Museum Herbarium. In September I’ll be going into my second year of my Neuroscience degree at the University of Manchester and I had decided to keep my summer busy and productive by gaining some valuable work experience. I can’t think of a Life Science which differs so much to Neuroscience than that of Botany, but I feel it is important to be open-minded in education and plant science is not a subject I neither have nor will encounter much due to the nature of my course.

I have been working here in the Herbarium for about 6 weeks now, thus nearing the end of my internship. I’ll be sad to leave, for it has been a fun and interesting experience working here and I have met some lovely people. It has been fascinating to see how the museum operates behind closed doors – something I would not have known without the internship.

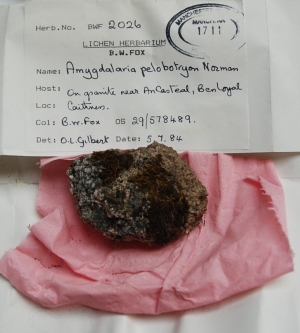

I’ve been helping both Rachel and Lindsey with photographing objects/specimens, cleaning and repairing specimen boxes, and putting specimens away. Primarily, I have been sorting through and documenting the British Lichen and Foreign Lichen collections onto the museum database. I have been recording the location of where each lichen specimen (if stated) has been found; usually converting town/county name to vice county number with the British lichens, and to country code for the foreign lichens. My geographical knowledge has improved considerably.

Lichens are organisms formed through a symbiotic relationship between a fungus and a phototroph (an organism able to make its own food from sunlight) such as algae or cyanobacteria. Symbiosis is a mutual give-and-recieve relationship between two or more biological species. The fungus provides protection and shelter to the phototroph, which repays the favour by feeding nutrients to the fungus. I was surprised at how variable the lichens are in shape and size – from flat ‘plate-like’ discs to long fibrous hairs. Lichens are valuable to the environment as they help prevent desiccation, and are good indicators of air pollution.

This entry was posted in Biodiversity, Herbarium History, Manchester Botanists, Students, Trees, Uncategorized.

![DSC_0057[1] Pressed Cylamen balearicum. Collected by Porta and Rigo, 1885.](https://herbologymanchester.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/dsc_00571.jpg?w=355&resize=355%2C200&h=200#038;h=200)

![DSC_0121[1] Marbled leaves of the Balearic cyclamen](https://herbologymanchester.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/dsc_01211.jpg?w=342&resize=342%2C608&h=608#038;h=608)