The Travelling Botanist

The Travelling Botanist: Cinnamon, a spice of many tales

Guest blog by: Sophie Mogg

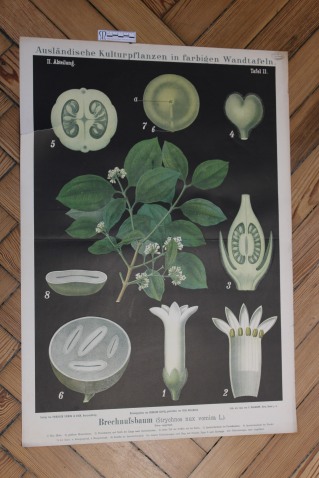

Cinnamon is a spice that we have all had the opportunity to try, whether in fancy coffees, liqueurs or delicious buns. Whilst the “true” cinnamon species is Cinnamomum verum, the most common source of cinnamon is Cinnamomum cassia. Both species originate in Asia, with C. verum being native to Sri Lanka (formerly known as Ceylon) and C. cassia originating in southern China. In order to distinguish the cinnamon produced by the two species in the spice trade, cinnamon refers to C. verum whilst cassia refers to C. cassia. This is because, C. verum is more expensive of the two due to its sweeter taste and aroma as less than 30% of cinnamon exports come from Sri Lanka.

Cinnamon has been traded for many thousands of years, with the imports into Egypt reported as early as 2000 BCE so it is no surprise that there are countless tales and historical events that surround this spice. From Sieur de Joinville believing cinnamon was fished from the Nile at the end of the world and Herodotus writing about mystical giant birds (such as a phoenix) that used cinnamon sticks to build their nests, the history of cinnamon is rich in legends of its origin as it wasn’t until 1270 that it was mentioned the spice grew in Sri Lanka. However as sweet as this spice may be it also appears to have a bloody history. Aside from the countless wars raged over the right to trade cinnamon, it was also used on the funeral pyre of Poppaea Sabina, the wife of Nero, in 65 AD. It is said that he burned over a years supply as recompense for the part he played in her death.

There are a total of 5 species (C. burmannii, C. cassia, C. citriodorum, C. loureiroi and C. verum) that produce cinnamon however C. verum and C. cassia are where the majority of international commerce is sourced from. Production of cinnamon is fairly straight forward albeit time-consuming. The outer bark of the tree is shaved off exposing the inner bark which is the cinnamon layer. This inner bark is also shaved off and left to dry, naturally curling as it does. By comparison the cinnamon of C. verum has a more delicate flavour than that of C. cassia as well as having thinner bark that is more easy to crush and produces a much more smooth texture.

Cinnamon is prominent in the practice of Ayurveda medicine as well as traditional Chinese medicine, being one of the 50 fundamental herbs. Traditionally it has been used to treat a wide variety of ailments from digestive problems, respiratory problems, arthritis and infections. In traditional Chinese medicine it is believed that cinnamon is able to treat these ailments through it’s ability to balance the Yin and Wei as well being a counterflow for Qi. These terms are aptly explained here for those who are interested. While there is little scientific evidence for the treatment of digestive and respiratory disorders, cinnamon does appear to possess antibacterial, antifungal and antimicrobial properties which may help to fight infections although at this moment in time it is inconclusive in studies trialled on humans. Cinnamon produced from C. cassia coumarin, which thins the blood, can be toxic to the liver in high concentrations so it is advised that only a few grams per day be consumed.

For those avid tea lovers out there I’ve found instructions to brew your own cinnamon tea.

For more information check out the links below

Cinnamomum cassia in Chinese medicine

Rainforest Alliance – Cinnamon farms

Leave a comment below to tell me what you think or what you’d like to see next!

The Poison Chronicles: Aristolochia -Childbirth Aid and Carcinogen

The Aristolochia genus is particularly close to the heart of the Manchester Herbarium, its name provides us a unique Twitter nom de plume. But it is also a plant with a considerable body count. It contains a carcinogen which may be responsible for a larger number deaths than more notorious plant poisons like cyanide and ricin.

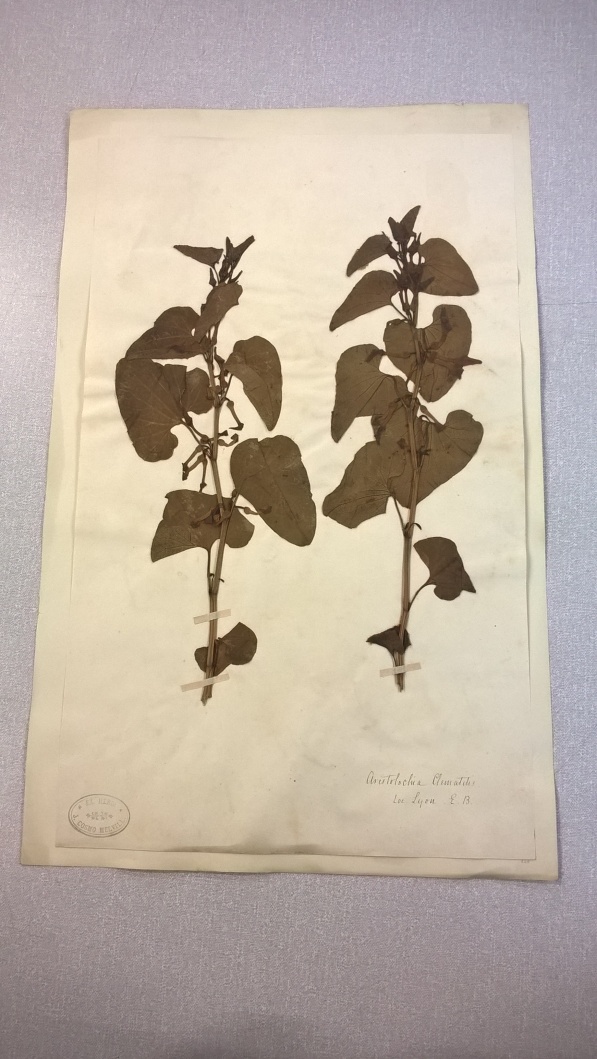

A number of species in the Aristolochia genus are known as birthwort. The genus name is derived from the Greek for “good for childbirth”, so both the common and scientific names suggests its medical use. It was noted by Roman doctors that the flowers of Aristolochia clematitis were somewhat womb-shaped. The Doctrine of Signatures, a major concept within the medicine of the time, stated that plants were designed to resemble the body part they could treat. Therefore A. clematitis roots were used for over two thousand years to trigger delayed menstruation, speed up a labour and help deliver a placenta. The plant continues to be used in Traditional Chinese Medicine and more rarely in homeopathy to treat a wide variety of diseases, despite the risks.

The roots of all Aristolochia sp. contain the carcinogen aristolochic acid, which for anyone can produce more mutations in the genome than tobacco smoke or UV light, but in the 5-10% of people who are genetically susceptible can cause kidney and urinary tract cancers. This was discovered when, in the late 1950s, localised epidemics of kidney disease and urinary tract cancer in certain rural villages in Bulgaria, Yugoslavia and Romania were noted. The condition was described as Balkan Endemic Nephropathy (BEN) but it’s cause was not found. However, in the 1990s a group of women with End Stage Renal Disease were all found to have taken the same herbal mixture for weight loss contaminated with Aristolochia fangchi, and their condition was described by researchers as Aristolochic Acid Nephropathy. When Prof Arthur Grollman from Stony Brook University learned this, he saw the similarities with BEN, and wondered if there was a similar cause. He found A. clematitis in the wheat fields of affected villages and the imprint of aristolachic acid damage in the DNA of BEN patients’ kidneys cells, showing a causal link between chronic exposure to Aristolochia and these cancers.

Aristolochia has been taken by many people as medicine or accidentally throughout history. As recently as between 1997 and 2003, an estimated 8 million people in Taiwan, were exposed to it in herbal medicine. This has lead some to suggest that it may be the most deadly plant in terms of number of fatalities rather than outright toxicity. Whether or not this claim could be quantified, it highlights that plants can be dangerous if used unwisely, so herbal medicines should not be taken blithely.

A. clematitis itself is a common weed, with creeping rhizomes and cordate (heart shaped) leaves. The distinct yellow flowers lack petals and form a tubular structure with a rounded base. Hardly notably uterine. The strange shape of the flower is due to it’s peculiar method of pollination. The hermaphroditic flowers begin first with the female stage and attract and trap flies within the flower, where they feed and spread pollen. In a few days the male stage produces the pollen that covers the trapped flies, which are released to pollinate again.

The native range is around the Mediterranean into central Europe, but was cultivated in the UK and USA. In the UK, it can be found as the survivors of the medicinal gardens of ruined nunneries and monasteries, a reminder of health care’s past and present mistakes.

For more information, see:

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/05/160503130532.htm

http://herbaria.plants.ox.ac.uk/bol/plants400/profiles/AB/Aristolochia

The Travelling Botanist’s #AdventBotany Day 21: Cornus mas

Guest blog by: Sophie Mogg

Seasons greetings from the travelling botanist, I’m taking a break from my travels to bring you a special blog post featuring in the advent botany. Today’s advent features Cornus mas. More commonly known as the cornerlian cherry, it is a medium-large deciduous tree of the dogwood family. Linnaeus referred to this species as both Cornus mas and Cornus mascula, translating to “male” cornel in order to distinguish it from the “female” cornel, Cornus sanguinea. It is native to South Europe as well as many parts of South Western Asia. It was thought not to be in the UK until 1551 whereby William Turner, a keen natural historian and friend of Conrad Gessner, heard that Hampton Court Palace had one in its gardens.

Cornus mas has a cold-hardiness rating of zone 4-8. The fact that it is so cold-hardy means that it is able to survive at temperatures between -25 to -30°C Celsius and is still able to flower at -20°C. The cold-hardiness has also meant that Cornus mas has been successfully introduced to countries outside of its native range such as Norway, Denmark and Sweden as well as across the UK.

Typically used as an ornamental plant, it is a bright and cheerful tree amongst the cold greys of winter. During autumn the glossy green leaves turn purple and come winter the tree boasts beautifully bright yellow flowers. The flowers appear around February to March and are typically very small (5-10mm in diameter) however they provide an important food source and a habitat for pollinators and other insects during those winter months. The flowers are replaced by green berries that ripen to a dark, rich red by mid-late summer. The berries swell to around 2cm long and 1.5cm in diameter and are very fleshy, containing just a single seed. The berries have been harvested and eaten for around 7000 years in ancient Greece, however as the small seed sticks to the flesh of the fruit it has been neglected by mass production and processing. Trees of this species are reported to live and still be producing fruit for over 100 years meaning that there are many years of bountiful harvests to be had if you find one near you.

When unripe the berries are often compared to olives however upon ripening they bear a tart flavour similar to that of cherries. Recipes from the 17th century detail pickling the berries in brine or serving them up in small tarts however the berries are also ideal for making into jams, sauces, syrups or even distilled into your own home-made liqueur or wine. According to Granny, cornelian cherry jams make a great a great alternative to other condiments with your turkey, but also suits cheese and other savoury dishes for this festive season!

I have listed some of the recipes below in case you happen to come across some of the cornelian cherry for yourself.

Turkish Cornelian cherry marmalade

A Travelling Botanist: Botanical Rainbow

Guest blog by: Sophie Mogg

With the latest installment looking at the cotton industry, I thought that it might be interesting to follow up with a few snippets about natural dyes derived from plants. In today’s blog post I will be taking a closer look at turmeric (Curcuma longa), true indigo (Indigo tinctoria) and madder root or dyer’s madder (Rubia tinctorum).

Turmeric belongs to the Zingiberaceae family which also includes cardammon and ginger. It is a herbaceous perennial that produces underground modified stems known as rhizomes which acts as a store for starch, proteins and other valuable nutrients. Rhizomes are useful in other ways as new plants can be propagated from the rhizomes that are harvested each year. The rhizomes themselves would be boiled for up to 45 minutes before being dried in a hot oven and ground to form a powder which can be used as a beautiful yellow dye. Unfortunately turmeric is not colour-fast and so was often over-coloured with mustard or various pickles to help compensate for this. Medicinally turmeric has reported uses in Ayurvedic practices for treating colds and infections as well as the Siddha medicinal practice where it is used as an energy centre due to representing the solar plexus chakra. Several studies have shown that turmeric also has antibacterial and antifungal properties with studies suggesting that turmeric could be used as a preservative in the food industry. Turmeric is also used in cooking for savoury dishes as well as the predecessor of litmus paper to test pH.

The native location of Indigo tinctoria is unknown as it has been cultivated for centuries across Asia and Africa. Indigo is a shrub reaching approximately 2M tall that produces flowers in various shades of pink and violet. Depending upon the climate Indigo is grown in it can be an annual, biannual or perennial. The deep blue dye that is produced from this species is obtained through soaking and fermenting the leaves which allows conversion of glycoside idican into indigotin (the blue dye). The dye has also been used within paintings dating back to the Middle ages. Indigo tinctoria is part of the bean family (Fabaceae) and so is also used within crop rotation by farmers in order to improve soil quality for subsequent crops.

The madder root produces various different coloured dyes ranging from reds, to pinks and oranges depending upon the conditions the plant was grown in and how the roots were subsequently treated. It belongs to the family of Rubiaceae, the same family as coffee and is a relatively tall perennial plant with evergreen leaves reaching heights of 1.5M. The dye is extracted through the process of fermenting, drying or using various acids to treat the roots, that are commonly harvested during the first year of a plants growth. One of the more commonly known dyes is referred to as madders lake, a dark red produced by purpurin being mixed with alkaline solutions. These dyes can be used to colour leather, wool, cotton and silk but are typically used with a fixative or mordant such as alum to help the dye fix to the material.

Tea can also be used as a dye, with different varieties of tea producing their own unique shades. With any kind of dye the colour will fade with time but it can be stabilised by using vinegar. As previously mentioned in my other posts both saffron and henna are used as dyes also.

Have your say in which species appear in future installments of the travelling botanist. Our journey will soon take us to South-East Asia where we explore some more intriguing plants.

You can find more information here: